Author: Mariia Semenchenko

Editor: Aliona Vyshnytska

Illustrator: ladada

Translator: Nadiia Matviychuk

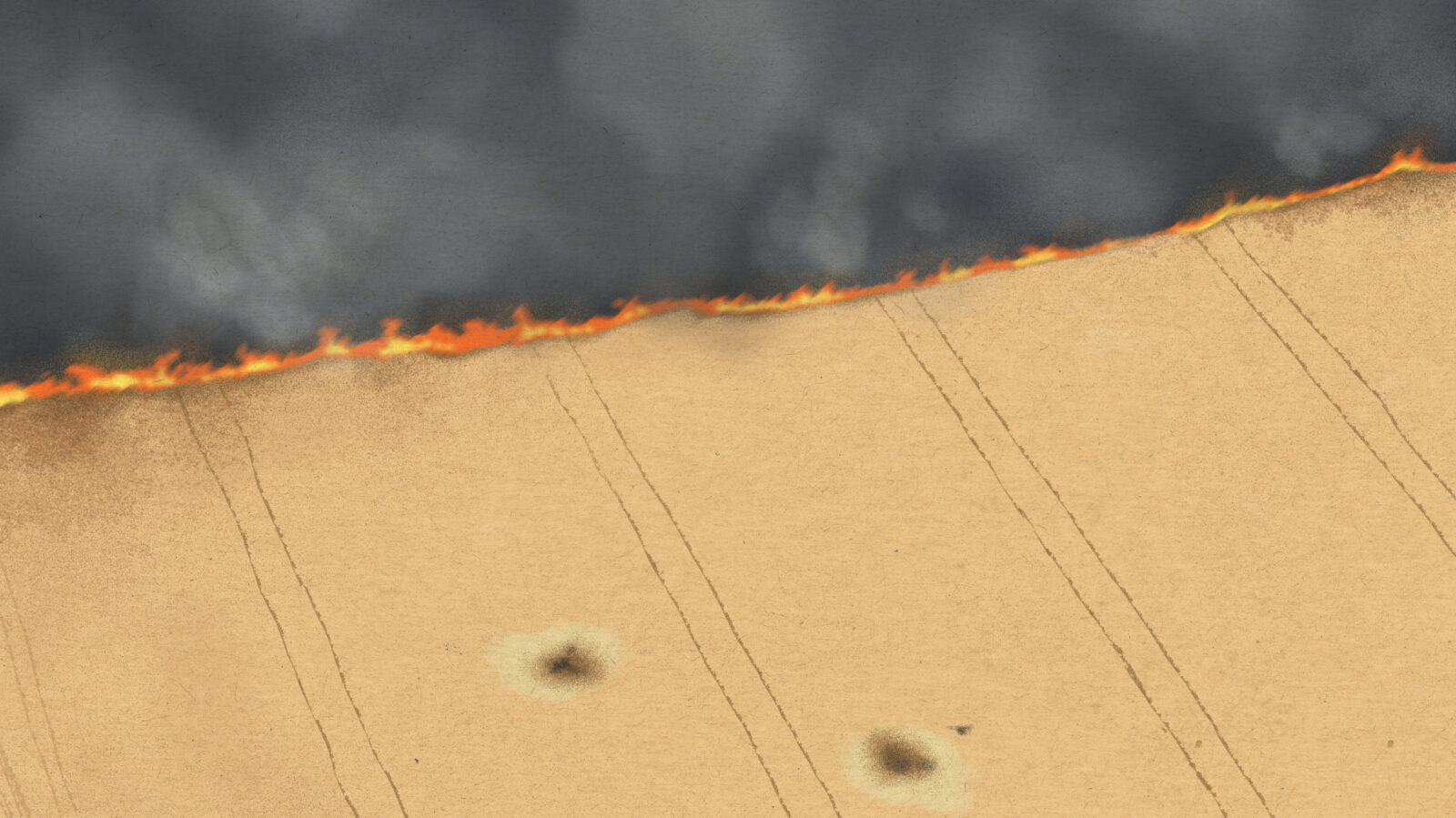

In the six months of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, human rights advocates and law enforcement officers have already recorded tens of thousands of crimes committed by the Russian military against Ukrainians which can be categorized as war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide. They include intentional mass murder of civilians in occupied cities, towns and villages (Bucha, Mariupol, Irpin, Chernihiv Region, Kharkiv Region, Kherson Region and other areas); kidnappings and torture of people; murder of prisoners of war; destruction and looting of property, private and public; sexual violence; forced deportation and filtration camps; using weapons of indiscriminate action; opening fire at green corridors, etc. Now Ukraine is already investigating almost 20,000 criminal cases of this kind.

According to the UN, as of early July, 4,889 cases of death and 6,263 cases of injury of civilians had been confirmed since February 24. “The actual numbers are much higher,” remarks the organization. The Russian military has already killed 358 children in Ukraine, and 681 children have been injured.

Russia defies international law and violates all the laws and customs of war. Russian troops commit all kinds of war crimes in the Ukrainian territory, purposefully intimidating and terrorizing the civilian population of Ukraine.

We are going to tell you three stories: about kidnapping, torture and murder; about torture and coercion to collaborate with the occupiers; about intentionally opened fire targeting civilians. Each of the stories is tragedy and pain for which Russians are to blame.

“I tried to feel around in the dark to find my daughter, but there were only stones under my fingers”

In a house in the Cherkasy Region, a big metal bowl drops on the floor. Two-year-old Anastasia hears it and starts screaming. Her scream is strong and inconsolable. Tears stream down her cheeks. Nobody can calm her down, neither her mom or dad nor her elder brother. “It’s banging! It’s banging!” repeats the girl. Nastia is scared of loud sounds. Nastia is one of the people who have survived the air strike on the Mariupol Drama Theater.

25-year-old Viktoria Dubovytska recalls the beginning of the full-scale war at her native Mariupol. She was just getting her kids—two-year-old Nastia and six-year-old Artem—ready to go to kindergarten when a neighbor called and told her that the war had begun, so they needed to stockpile water and food. Explosions could be heard in the city. Viktoria’s family lived in a detached house without a basement or cellar. Her husband, Dmytro, wasn’t with them: he was working in Poland. “We’d just started renovating the bathroom. There was a hole in the floor covered by wooden planks, so I took the planks off and put the kids in the hole, covering them with an upside-down bathtub,” recalls Viktoria. “Power and gas were cut off almost right away, it got cold in the house.”

Viktoria and her kids went to the seaside apartment of her friend who also lived there with a young child. Their house had an organized cellar. “Starting on March 3, we no longer had any power or cell connection. There were already major bombings, but on that day it was rather quiet, so we took the kids and went out for a bit to get some air—and we managed to catch a weak cell signal. My friend reached her husband, he said there would be evacuation from the Drama Theater,” recalls Viktoria.

The evacuation was disrupted. “We could no longer go back, the Russian bombing of the city was intensifying, so we decided to stay at the Drama Theater,” says Viktoria. “The basement was already crowded, so we found a spot in the corridor between the columns. We were told right away that we should not go onto the stage under any circumstances, because there was only a dome without a concrete ceiling above it. Although many people did go up there because it was warmer.” The theater employees told people to take the curtains and seats from the hall and arrange places for themselves, because it seemed like they were all stuck there for a while.

“The first days were the hardest because nobody could figure out where to get food. Some people came without anything at all. We took about a kilo of apples, three liters of water and a few packs of biscuits and candy. The things we were supposed to eat on the road. They lasted us three days. And then there was nothing. The kids were crying, saying that they were very hungry. And on the fourth day, our soldiers from Azov found out that there were children in the theater. They thought people were only in the basement, but it turned out that the entire theater was full—several thousand people were sheltering there. They brought us boxes of frozen offals, chicken heads and legs, fish heads. The things we fed to our pets in peacetime were now saving our lives. People cooked some kind of soup from these things in the kitchen to feed the children first and foremost. A field kitchen was organized outside.”

Viktoria remembers that if there was any food left, then the women were fed, while men had to get food for themselves on their own. This sometimes caused conflicts because everyone was hungry and scared. They quickly ran out of water. Viktoria recalls that at that point the theater workers opened the service water pit.

“It had been stored there for a year or two, it was gray, dirty. This water was boiled and used for cooking, and given to the kids to drink. But even after boiling, it was still cloudy, and a layer of gray mud settled at the bottom. But we didn’t have any other water,” says the woman. Whenever the bombing got a bit quieter, men would go out to the nearest stores and pharmacies to try and find some food or warm clothes. Sometimes they brought cookies and chips and gave them out to the kids.

“The theater was unsanitary, people started getting sick. Nobody washed, we couldn’t even wash our faces, we didn’t do laundry. My friend and I had two-year-olds in diapers, but there was no way to wash the babies. We asked other people for napkins to at least wipe the children’s hands. The kids were all thin, dirty, in a horrible state. We were trying to survive,” says Viktoria.

Little Nastia soon contracted pneumonia, and the family were moved to the lighting room on the second floor, right opposite the stage. The narrow window up there was covered with plywood. Viktorial laid a curtain on the floor as a makeshift bed. On March 16, a Russian aircraft purposefully dropped a bomb on the Drama Theater, even though there were huge letters spelling “Children” outside the building. When this happened, Viktoria had just brought the kids to the lighting room to give them some food.

I seated Nastia on the floor, and the boys were standing a bit to the side. As soon as I walked up to the table, there was a very loud sound. I was thrown to the opposite wall and hit my face. It was the bomb that fell on the stage. Rocks started raining down, I heard the boys scream. I didn’t hear my daughter at all. I don’t know how long it lasted, maybe a few seconds? I took a flashlight out of my pocket, lit the space and saw the terrified boys, Tioma and Nazar. They had all their limbs and there was no blood. Then I started looking for my daughter. I tried to feel around for her, but there were only rocks under my fingers. Those were the most terrifying few minutes in my life. And then she cried, “Mommy!” And I dug her out. She was saved by the blankets I folded after sleeping, they were the first to fall on her, followed by rocks on top,” retells Viktoria.

The woman recalls how she grabbed the kids and ran. People were lying on the stairs, everywhere was blood, debris, dust. She met her friend on the ground floor, and they decided to run. Their acquaintances said that they should not go to the kitchen: “There’s no-one there anymore. Everyone’s been killed.”

They ran out of the theater and rushed away without looking back. “We heard shelling and machine gun bursts. Shops were burning at the central market. The kids saw dead bodies lying in the streets for the first time. It was an area under heavy fire. We realized that if we stopped, we could die,” recalls the woman.

As we were running, we saw Russian soldiers and asked, ‘We’re from the Drama Theater, why did you bomb it?’ And they replied, ‘We got an order, so we did it.’ They knew perfectly well that there were children inside, that there was no military in there.”

They reached a school in another neighborhood, and in a few days they were able to leave Mariupol for the occupied Volodarske. There were no other options to leave the city.

“My husband didn’t know if we were alive. He took a leave from work and went to look for us. He thought that he would either find us alive or at least bury us properly if we were dead. On March 22, people took us to Volodarsk, and on March 23, my husband arrived in Mariupol to look for us.” He found them.

Now the family lives in a village in the Cherkasy Region. Dmytro works in Kyiv as a security guard. Viktoria looks after the kids and the household. “Nastia is very scared of loud sounds, and Tioma had an episode already back in the Drama Theater. He woke up and didn’t know who he was, where he was, he was constantly calling for his mom but did not recognize me. He didn’t recognize anyone. And when he finally came around a bit, he cuddled up to me and said, ‘Mom, I want to live so much.’ A doctor later explained to me that it was a protective response of the mind,” says Viktoria. “The kids got so thin. I could see Tioma’s ribs, his belly was sunken. We let the kids recover gradually, following doctor recommendations, because at first they would vomit from regular food.”

Viktoria recalls how she visited the Drama Theater as a child, and later with her husband.

“And even more often we would just walk around the Drama Theater, concerts were organized there, a wonderful fountain was built, and a playground. It was a nice place to go for a walk with your family,” she says. “And now there is no Drama Theater, and no city either.” She misses home and her grandmother who died of a stroke in the occupied city. She says, “Everything has been taken away from us. We have to start life from scratch, and live the way we want to, without fear, because we have nothing to lose.”

War crimes have no time limitation, explains Anastasia Nekrasova, a lawyer at the Ukrainian Helsinki Human Rights Union. A characteristic feature of the Russian invasion of Ukraine is intimidation of civilians and attacks against them. “To put it roughly, Russia is waging war against the civilian population of Ukraine,” explains the human rights advocate. “In addition, there are signs of crimes against humanity or genocide. These are also war crimes which, however, are mass and systemic in nature—meaning that they are not just isolated incidents but a conscious policy of killing the civilian population. In this case, responsibility will also be borne by the top leadership of the aggressor state. This war is not an internal conflict, it is a threat to global peace and security, so it is significant for the entire global community.”

In their investigation, the Associated Press noted that as a result of the Russian attack on the Drama Theater in Mariupol, about 600 people were killed inside and outside the building. The survivors estimate that about 1,000 people were inside the theater when it was bombed, and 200 were able to escape.

In total, at least 22,000 people died as a result of Russian aggression in Mariupol—this number was provided by Petro Andriushchenko, advisor to the mayor of Mariupol. Most of the victims were buried in mass common graves near the villages of Staryi Krym, Manhush and Vynohradne, according to the Mariupol City Council. According to the Council’s estimate, about 16,000 people are buried there. Bodies are laid in several layers and then “masked” with signs as if they were individual graves. About 5,000 more people had been buried by city services by mid-March. There are still bodies of killed city residents buried under rubble, in makeshift graveyards, and left in temporary morgues.

Over 50,000 Mariupol residents have been deported to Russia and the temporarily occupied territories of the Donetsk Region. Today, over 100,000 residents are still living in the blockaded city. Mariupol is under the threat of an environmental disaster and infectious disease outbreaks. In addition, the Russian invaders have damaged or destroyed 1,368 residential buildings in Mariupol which were home to over 156,000 residents. Over 60% of Mariupol’s apartment buildings have been damaged by more than 40% or destroyed completely.

“His face was a bloody mess”

On May 22, a young man came to a city pier in Kherson to catch some crayfish. He later recalled that the weather was cloudy, and suddenly the clouds were pierced by sun rays that lit up the fairway. The water there is up to eight meters deep, but the diver clearly saw something at the bottom: first some bright spots—red-and-white sleeves of a men’s jacket—and then a person, tied up with a kettlebell attached to their legs.

“I saw this horrible news online, that someone found a person tortured to death at the bottom of the river—with their skull smashed and a weight tied to their legs, but I didn’t think that it was my Vitalik,” Olena Lapchuk’s voice is trembling. “Since March 27, I hadn’t had any information about my husband, I felt that the Russians had killed him, but I still had hope. Now I’m grateful to God that we’ve found his body. Because he could have been caught by a boat and dragged away, and then we’d never find out what happened to him…”

Vitaliy Lapchuk was 48. He was born in the Lviv Region, but he lived most of his life in Kherson Region (when Russian soldiers see the place of birth in Vitaliy’s ID, they’ll be happy to have caught a real “bandera”). Vitaliy graduated from the Lviv Military Institute and served in a landing battalion in Mykolayiv. That was when he met Olena: she was building a gas station in Kyselivka, a village which Vitaliy passed on his way to visit his parents in the Kherson Region.

“A young, handsome military man—how can you not fall in love?” recalls Olena. “He was a wonderful person. Everyone loved him, especially children, all cats and dogs in the street always approached him. He was kind, but at the same time he had military training: everything had to be done honestly and properly. He had an acute sense of justice.”

Vitaliy and Olena got married and built a house in Stepanivka, a suburb of Kherson. They worked a lot: Olena was growing her business, Vitaliy was the head of the Kherson Department of the Odesa National Internal Affairs University, he defended a PhD thesis in legal psychology. They were bringing up two sons. In the past few years, Vitaliy worked in Kyiv in the State Reserve.

“We lived a whole life together, 26 years, and it was a beautiful life,” says Olena Lapchuk.

On the first day of the full-scale war, when the Russians were already bombing the airfield across the field from their house, Vitaliy came to Kherson, to his family. The next day, he headed for the Antonivsky Bridge, where battles raged the day before. “There were so many bodies—our military and civilians! He saw a killed Ukrainian tankman, very young, he brought a blanket from the car and covered him. In the cars, there were families, children shot dead. He photographed everything,” recalled Olena. “Nobody in the city knew what to do, chaos was everywhere. Then Vitalik said, ‘I have to defend Kherson,’ and he went to the military recruitment office.”

At the military office, he met Denys Myronov, who was also later tortured to death by the Russian military. When the military recruitment office rejected them, they signed up for the Kherson Territorial Defense, where they formed their company together with Kherson civilians. “Vitaliy was the company commander, and Denys was his deputy. They had 59 people under their command. They never showed the lists with the guys’ information to anyone, and that way they saved them. They didn’t give away their people even under torture.”

In early March, Russian troops entered Kherson. The bodies of the killed Territorial Defense members who went out to intercept a Russian heavy equipment convoy with just automatic guns and Molotov cocktails were found in the Lilac Park in the Shumensky neighborhood. Some didn’t even have any bodies left, just fragments.

Vitaliy and Denys started driving to the bread factory and loading up a trunkful of loaves which they then handed out to elderly people. They also looked for abandoned weapons. “They hid them under the bread and drove them through Russian checkpoints. They figured that the weapons would be needed when Kherson is being liberated from the occupiers,” says Olena. “They also passed the coordinates of the exact location of enemy equipment to the Ukrainian army. But somebody betrayed them, somebody Vitaliy trusted.”

On March 27, Vitaliy Lapchuk and Denys Myronov took cans and headed out to look for fuel, which the city had almost run out of by then. A few hours later, Olena Lapchuk suddenly felt sick: her vision went dark, she felt dizzy and nauseous. Olena was at her mother’s house, where her elder son was also visiting (her younger son lives abroad). She kept calling her husband, but first he wasn’t picking up, and then his phone went offline. At 1 p.m., three Jeeps with Zs painted on them drove up to the house. Olena’s phone showed the name, Vitalik: “Olena, open the gate for me, they’ll take the weapons.”

The woman approached the gate, her legs barely obeying her.

I saw Vitalik’s face—it was black. His jaw was completely broken, his cut eyebrow was bleeding into his eyes. His face was a bloody mess. His jacket was soaked with blood,” cries Olena. “Nine men, armed to the teeth, entered the yard with him. They even had gas masks. I even thought, ‘why do they need gas masks, are they going to poison us?’”

Olena recalls that she started yelling: “Who are you, where from, what’s your unit, names? Why have you come to my house, you know that you’re occupiers, right?”

“I kept repeating that none of them was worth a pinkie from Vitaliy’s hand. And then one of them, with these stupid glass eyes, said, ‘Another word from you and you’ll clench your teeth,’” recalls the woman.

On the way to the basement, they broke Vitaliy’s face bone with a rifle butt. Olena remembers that her husband was barely alive. She recalls her mom screaming, pressing a Bible to her chest, begging them not to touch Vitaliy. She recalls how the Russians entered the house to take everything out, from laptops and phones to perfume and socks. “They even took golden dental crowns my mom kept at home, and all of mom’s savings,” says the woman. They also took the weapons which Vitaliy and Denys hid there, and two American rifles of Olena’s grandfather, who was a hunter. And they took the cars that belonged to the couple.

“And then they said, ‘You’re all terrorists and nazis, you’ll come with us.’ We managed to defend mom, so they didn’t take her anywhere, an elderly woman who had just survived a difficult illness,” says Olena. They left her mother at home, but soon her yard was hit by a cluster bomb. The only thing that saved her was the fact that she was in a different part of the house at that moment.

“When they were pulling a bag over my son’s head and tying his arms, I caught Vitalik’s gaze. He looked at me as if he was apologizing for what happened, as if he felt guilty for what was going on,” weeps Olena Lapchuk. “I wanted to support him, say that it was nothing, we would manage, everything would be alright. I didn’t know back then that this would be his last glance.”

The family was taken to the building of the Regional Police Department in the Kherson Region. All three of them were interrogated in different rooms. Only one wall was between Olena and Vitaliy, and she heard what they were doing to him. Her son and she were photographed after the interrogation, their fingerprints were taken, and they were led into a room where other people with bags on their heads were kept. Olena was drenched, tears and sweat were soaking her clothes. It was hard to breathe because she had a bag on her head. It was hard to breathe because Vitaliy was being tortured beyond thew all. She recalls how the Russians called each other by their callsigns.

“There was a Demon and an Angel among them, and I thought, how can there be any angels here, only demons,” says Olena.

Olena and her son were released: taken to the bridge and thrown out of the car. The woman managed to ask them: “Where is my Vitalik?” And they said that he confessed to terrorism, and now he would be tried according to the law of the Russian Federation.

When Olena and her son finally reached their house, they saw that it was hit by a missile. Of the entire street, only their house. “It’s the house we’re registered in, they saw the address in our IDs. The missile broke through the roof, ruined the stairs. We entered the house, it was full of dust everywhere, debris, bricks. And the carpet was smoldering,” recalls Olena. Then she realized that today they were released, but tomorrow the Russians will look for them again. Her son went to stay with his friends, and Olena took her mother and also went to stay with her friends. There, she immediately described everything that happened to them on social media.

“I planned to stay in Kherson a bit more, I thought I’d be able to help Vitalik somehow. Volunteers and I called all the hospitals, he was beaten very badly, and I thought they would provide medical care,” says Olena. “Later, when we’d already left the city, I hoped that he was in Crimea where he would be tried. We combed through the entire Crimea, we wrote to the Red Cross in Tambov and Rostov. But there was no trace of Vitalik anywhere. No trace.”

The Lapchuks managed to leave occupied Kherson in the morning of April 7. They were driving with friends who had small children. Their cars came under fire, but they survived, only the cars were damaged.

This whole time Olena was looking for Vitaliy, until, on June 9, she found out that the tortured man from the river was him. Vitaliy was buried next to Olena’s father and brother. She cries that she couldn’t even say goodbye to him. “When we de-occupy the Kherson Region, we will be horrified at the scale of terror that is going on there. People are robbed, kidnapped, tortured!” says Olena. And, after a brief pause, she adds: “We are all really waiting for the liberation of the Kherson Region. I only have one plan: to return to my hometown. I will restore my house, I will live. I really want to go home.”

Since the beginning of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the law enforcement in the Kherson Region received almost 500 reports about kidnappings. According to the Kharkiv Human Rights Group, as of late June, 286 people were kidnapped and their fate remains unknown. Another 68 people were kidnapped and released in a few weeks. In addition, the occupiers took 58 orphaned children from Kherson and drove them in an unknown direction.

A report by the Human Rights Watch describes that from the first days of the occupation, Russians detained and kidnapped Ukrainian military servicemen and Territorial Defense members, public officials, police officers, veterans, journalists, activists who opposed the occupation, volunteers, and later they started kidnapping random people.

“Russian troops have turned the occupied areas of Ukraine’s south into an abyss of fear and wild lawlessness,” stated Yulia Horbunova, senior researcher for Human Rights Watch in Ukraine.

“Russians break people, I’ve had first-hand experience of that”

On March 2, 2022, Father Serhiy Chudynovych, the prior of the Kherson Saint Intercession Temple of the Orthodox Church of Ukraine, was standing in the middle of a cemetery just a kilometer from the Chornobayivka Airfield, in the field. He saw a convoy of heavy Russian military equipment driving on the road. He knew that if the Russians wanted to, they would easily shoot the people in the cemetery, who were very well visible. On that day, they were burying members of the Kherson Territorial Defense: 67 men who were killed earlier in the Lilac Park and Shumensky neighborhood. The head of the communal undertaker service of Kherson was driving, bringing the bodies, no more than eight per trip. Several gravediggers were quickly digging graves. Father Serhiy Chudynovych was reciting prayers over the deceased and helping to lower them into the graves.

“Russians were entering the city from different directions, they had heavy equipment. Territorial Defense members, civilians without any experience, equipment or weapons began ad hoc defense. They were in the park, carrying Molotov cocktails in plastic bags. They were all just shot, like at a shooting gallery,” recalls Serhiy Chudynovych and shows us photos: fragments of a body, entrails in a dark plastic bag. “Not everyone could be identified. Some had their papers with them, but the majority didn’t. We photographed the bodies from different angles, tried to record bright details on their clothes, some kind of inscriptions, fastenings, stripes, something that could later help identify a person. We wrote down whom we put in which grave.”

Serhiy Chudynovych remembers that at that moment, when he was reciting prayers over the mangled bodies of Kherson defenders, he did not feel anything. “I was in this cold state, there were no emotions whatsoever. As if I was looking at it from the outside. My shock from that cruelty, that atrocity transformed into rational fixation of this fact,” he says.

Before going to the cemetery, Serhiy Chudynovych gave all the necessary instructions at the church—in particular, he indicated the spot where he wanted to be buried. He didn’t know if he would come back alive. People had already been kidnapped and killed in the city.

From the first days of the war, the Saint Intercession Temple in Kherson became a major social center. “My main task in Kherson was to mitigate the panic and call on people to be calm, because only in that state a person is able to think rationally and act effectively,” recalls the priest.

The church started hosting a parish hairdressing salon, a cafe and a food warehouse. Plus a medicine cabinet where they began to stock up medications from the first days. At first they were collected in Kherson, and then Father Serhiy Chudynovych started driving to Mykolayiv across the field, along the shore. He hoped that the invaders would not touch a priest.

“For instance, the hairdresser’s. Imagine, someone rushes into the church all panicked, crying: what should I do, Father? And I tell them: let’s give you a haircut first. And right then, they get some distraction,” explains Chudynovych.

On March 30, he came to the temple. Before entering, he would always clean his shoes to show the parish members that they should live their usual life even under these difficult circumstances. Suddenly he felt someone standing behind him. It was a man wearing a military uniform and a balaclava, and other men wearing medical masks next to him. Serhiy Chudynovych understood everything. He was put in a car and driven to “have a conversation.” With every minute passing, the conversation was becoming more and more brutal.

“I was accused of participating in sabotage and reconnaissance groups of the Ukrainian army. They asked if I wanted peace, what I thought about the veterans of the Great Patriotic War [Russian name for World War II. Ed.]. I said that yes, I wanted peace, but peace as a result of the Ukrainian victory over the Russians. Then they pulled a hat over my face and tied my mouth and nose with a kerchief,” recalls Serhiy Chudynovych.

He was led into a dark cold basement. They wouldn’t give him water or take him to the bathroom. They constantly threatened to do something to his family if he did not agree to collaborate with representatives of the Russian Federation.

They twisted my arms, said that my life was over, that they would kill me, shoot me, cut me into pieces. They brought me to a different room. There, they started hitting me with a club in the area of my heart, demanding some kind of information from me. They hit me on the legs, choked me. My mouth was so dry, I couldn’t talk, I asked for some water, but they gave me vodka. They undressed me, put me on my knees, pressed my head to a seat, took a club and said that they were going to rape me with it. I didn’t know what to do, I said goodbye to life, I was praying. I was very scared,” recalls the priest. The occupiers used torture to force him to sign a document about “voluntary collaboration.”

“I’m ashamed that I showed weakness. I got scared. I hope that the Ukrainian state and people will forgive me for this weakness,” he says at the end of a video he published on social media.

Serhiy Chudynovych told everyone that he was going to Mykolayiv to get some medicine on April 7, but instead he left the city on April 6, introducing himself at checkpoints as a Moscow Patriarchy priest. The first thing he did in the territory controlled by Ukraine was go to the police, where he told the officers everything that had happened to him. That he did not collaborate with the occupiers, and he was forced to sign the document under torture.

Now Father Serhiy Chudynovych serves between Odesa and Kryvyi Rih. He doesn’t have his own church, often serves mass online. He also continues to do social service: he collects medications and medical equipment, including items from abroad, to send them to local health care institutions. He keeps in touch with his temple in Kherson. Only one of its 19 workers have remained there. Food is cooked and distributed among Kherson residents there. Kidnappings and torture of people in the city never stop.

“The Russians are creating their own kind of reality in which no freedom exists whatsoever. They truly believe what the propaganda tells them. They really break people, I’ve had first-hand experience of that. I was so terribly paranoid in May: I couldn’t sleep, changed all the phones, passwords, everything. It was scary,” says Serhiy Chudynovych. “I took it all very badly. Now I talk to God very easily, I’m not afraid to talk to him. Only lately have I been looking at the heavens in silence. Everything is clear without words.”

In the temporarily occupied territories, the Russian military persecutes priests, mostly those serving in the Orthodox Church of Ukraine. They are kidnapped, tortured, coerced into collaboration. Ihor Onchev, a priest of the Orthodox Church of Ukraine from Chernihivka, Zaporizhia Region, spent nine days in captivity. Vasyl Vyrozub, a priest from the Odesa Region, spent 70 days in captivity. Oleksandr Chokov, the chaplain of the 35th Separate Marine Brigade, was kept prisoner by the Russians for almost three weeks. Another chaplain, Leonid Bolharov, was a prisoner of the Russians for 43 days. A priest from Bohdanivka, Kyiv Region, was kidnapped and brutally beaten. Russian soldiers killed Maksym Kozachyna, an OCU priest, near Ivankiv, Kyiv Region.

The occupiers believe that priests are the ones who can organize the resistance movement in the occupied territories, accuse them of spying, sabotage, and helping the Ukrainian army. They also try to coerce priests into collaboration in order to have influence over the local community through the priest.

In addition, the Russians purposefully target Ukrainian churches of different denominations and prayer houses with their strikes. In Mariupol, they bombed a mosque where about 80 civilians were hiding. During bombings, members of the clergy are often killed or wounded.

Detention, kidnapping, torture and murder of the clergy, just like any other population category, is a war crime. Damaging or destroying religious buildings (churches, mosques, synagogues, etc.) is also a war crime.

The project is produced with the support of Lviv Media Forum and EU-funded programme House of Europe.