Illustrated by Дар’я Бороденко

“A woman ran to our bomb shelter and asked for help: her husband had stepped on something and both his legs were torn off. Svitlana, a woman from our basement, helped put that man in the car, took the couple to the hospital, returned, parked the car at the entrance and came back to the bomb shelter. All of that was done under continuous shelling, risking her own life every minute.”

Khrystyna Jolos, her husband and son were among the first to leave Mariupol. The family spent 16 days in a bomb shelter, almost without leaving. Every outing could cost them their lives.

“On March 15, my family and I managed to leave Mariupol. There was neither a green corridor nor organized rescue. We did it at our own risk. At the beginning of the war, active shelling was on the outskirts, in the center—it was scary, but we could still live somehow. Back then, few people were leaving the city, the local authorities did not inform us about anything like that.”

There are few bomb shelters in the city: most of them are basement floors of buildings, there is a catastrophic lack of basements with ventilation.

“We were hiding at the grammar school where my son was studying. It was the ground floor, cold and wet. At first, we only stayed overnight, sleeping right on the floor. During the day we returned home under fire, there was still electricity and gas, and food could be prepared. People from the outskirts were moving to the center. I cooked soup for them, tried at least a little to support those who were left without anything. It wasn’t a matter of survival yet, everyone was helping our military and each other quickly and actively.”

The family came under fire one time when they were returning home. “The windows have been knocked out in our house, a shell has fallen into the yard. When I got to the entrance, I heard that another shell had arrived. I threw my son to the ground, right on the broken glass, covered him with my body. We got out alive, but we didn’t go home anymore. From this day there was no light.”

Khrystyna tried to catch a mobile connection and to do this she went out to the city. Neighbors in the bomb shelter handed her a paper with phone numbers and asked her to give messages to their relatives. “There were many people and cars near a store called 1000 Trifles, which is well-known in Mariupol. Suddenly, a stronger shelling began: many shells fell into the crowd. Then I first saw a corpse lying on the road.”

Bonfires were burning in the yards for people to cook soup or heat water. Shells arrived from time to time. One of these times a man had his leg torn off. He was lying there bleeding, but there was nobody to take him away. Another shell knocked out some of the windows in the bomb shelter where Khrystyna’s family was staying. One woman was wounded in the thigh, she was lying on the ground floor all night begging people to give her poison so she didn’t have to feel the infernal pain.

“People were digging common graves, just burying the corpses in shallow holes. It was recommended to carry those who died a natural death out onto balconies. Nobody was taking anyone out. If a child was sick, it was impossible to predict what would have happened to them. Everyone was sick because it was very cold sleeping on the floor. There was a one-year-old girl in our shelter whose fever rose to 40 degrees. Everyone was looking for any kind of medicine for her, but no antibiotics were found.”

It is still unknown whether she has survived.

The family decided to flee. They got to their apartment under fire, grabbed their cat and a suitcase which they had packed hoping for a green corridor. They printed out and pasted the sign “Children” on their car window. “You don’t know if you will reach your destination or not. People were screaming nearby. It was difficult to describe and comprehend what was going on, there was chaos and disorder”.

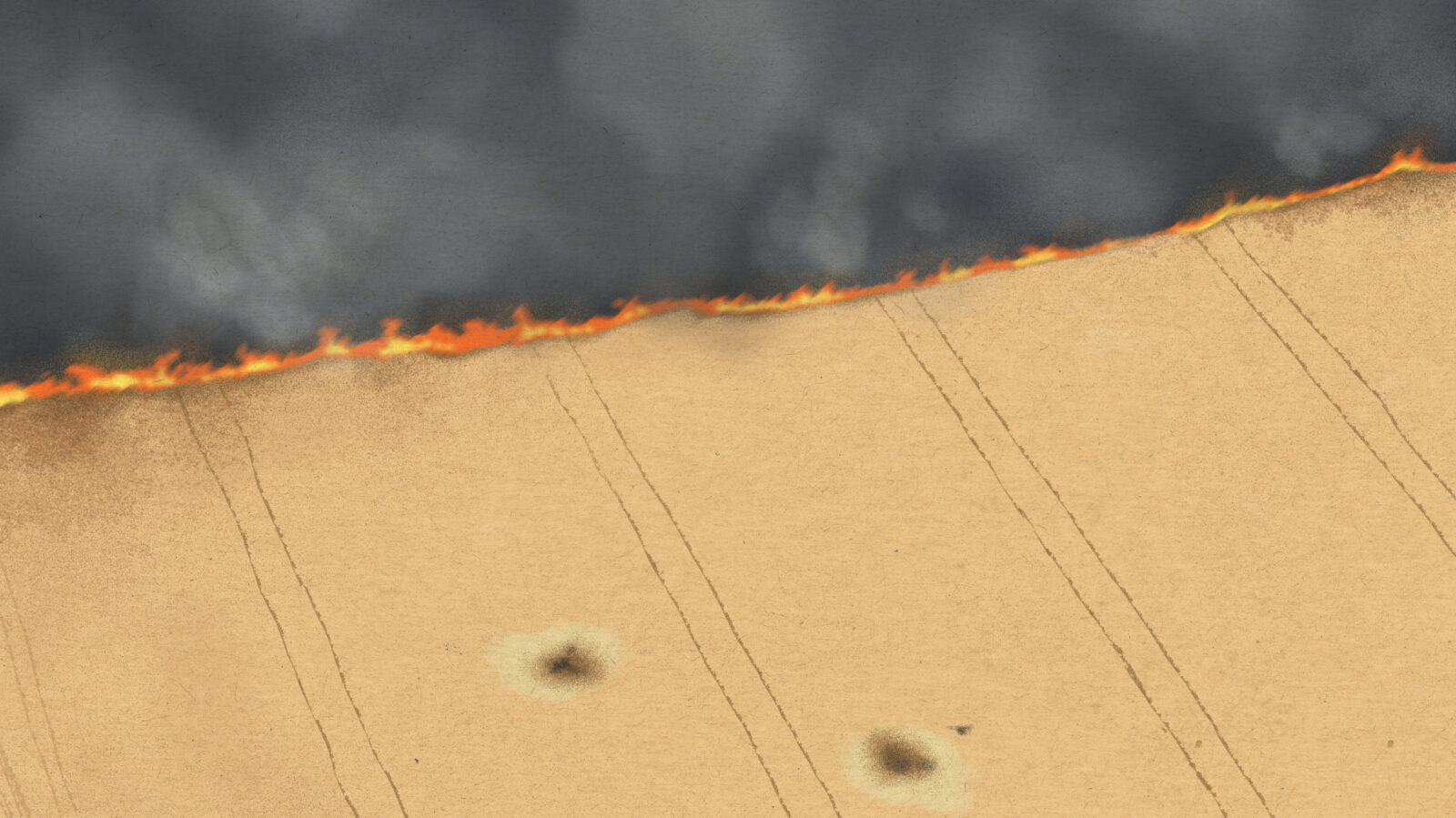

Cars formed a column to keep together. They were passing broken wires, destroyed houses, enemy planes were flying above them, they constantly heard shelling. On the way out of the city there were traffic jams and Russian checkpoints. The occupiers examined the cars: “My husband even had his fingers checked: I think they wanted to see if he had been shooting a gun. It was incredibly scary, but we didn’t hear the explosions anymore.”

The curfew caught the family in the middle of a field in the gray zone, between the invaders and Ukrainian troops. Together with other cars, Khrystyna’s family stayed overnight. It was cold, but fuel had to be saved, so the family were keeping warm under blankets. At 5:30 a.m. they drove off, got lost a bit, but finally they found a Ukrainian checkpoint.

“There are thousands of people left in Mariupol, I don’t know how to help them. My mother and three brothers are also still in the city, hiding from shelling in the basement. No one can get there and pick them up.”

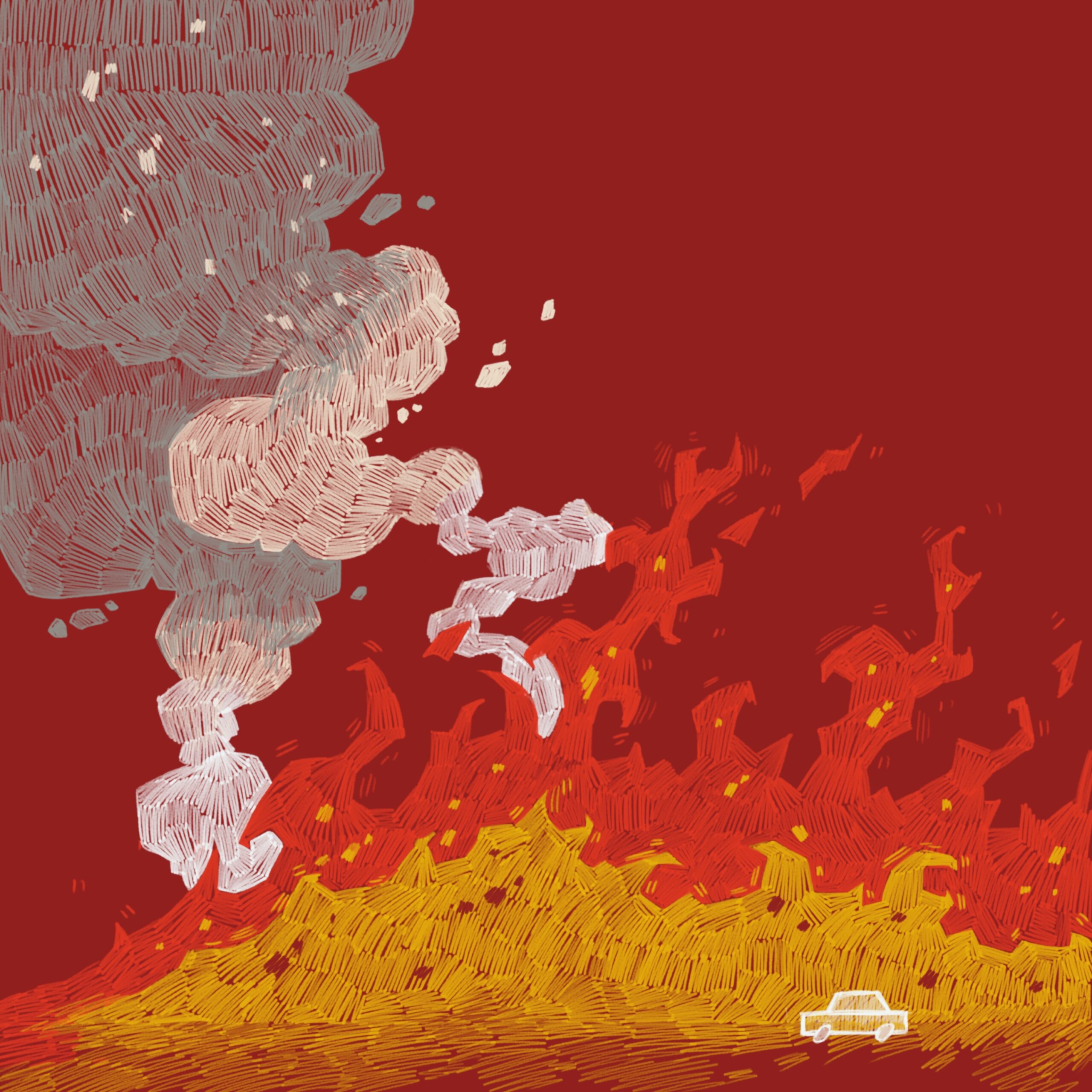

Khrystyna dreams of hearing the voices of her loved ones and wants the shelling to stop. “We will never feel at home anywhere anymore. All our previous experience, the trifles and loved ones dear to our heart have remained at home. My home, Mariupol, now looks like a fiery hell soaked with fear and hopelessness. A hole that burned everything that mattered to us.”

Translated by Olesja Yaremchuk