Author: Maryna Kuraptseva

Illustrator: Olha Panteleimonchuk

Dmytro Pasternak, a tenacious traumatologist, had dedicated years of his life to serving in Donetsk, tirelessly working at the regional traumatology hospital and imparting knowledge at the medical university. In December 2014, he decided to begin anew in Mariupol, excitedly building a new life, but little did he know that the russian invasion would shatter all his plans and dreams.

The Vostok SOS Charitable Foundation has been collecting information on war crimes committed by the russian federation since 2014 to ensure justice and the right to truth. The story of Dmytro Pasternak was recorded for the publication “War. Stories from Ukraine” by Mariia Biliakova and Nataliia Kaplun. The text is written by Maryna Kuraptseva.

My family and I lived on Bakhchyvandzhy Street until February 2022, a period of five years. Mariupol was flourishing, and we felt secure, believing there would be no major conflict. However, when it began, my colleagues and I made the decision to stay and defend the city.

On February 24, I went to work as usual. The first wounded civilians and Ukrainian soldiers were transported from Nikolske, which had suffered a devastating attack. The number of victims increased with each passing day.

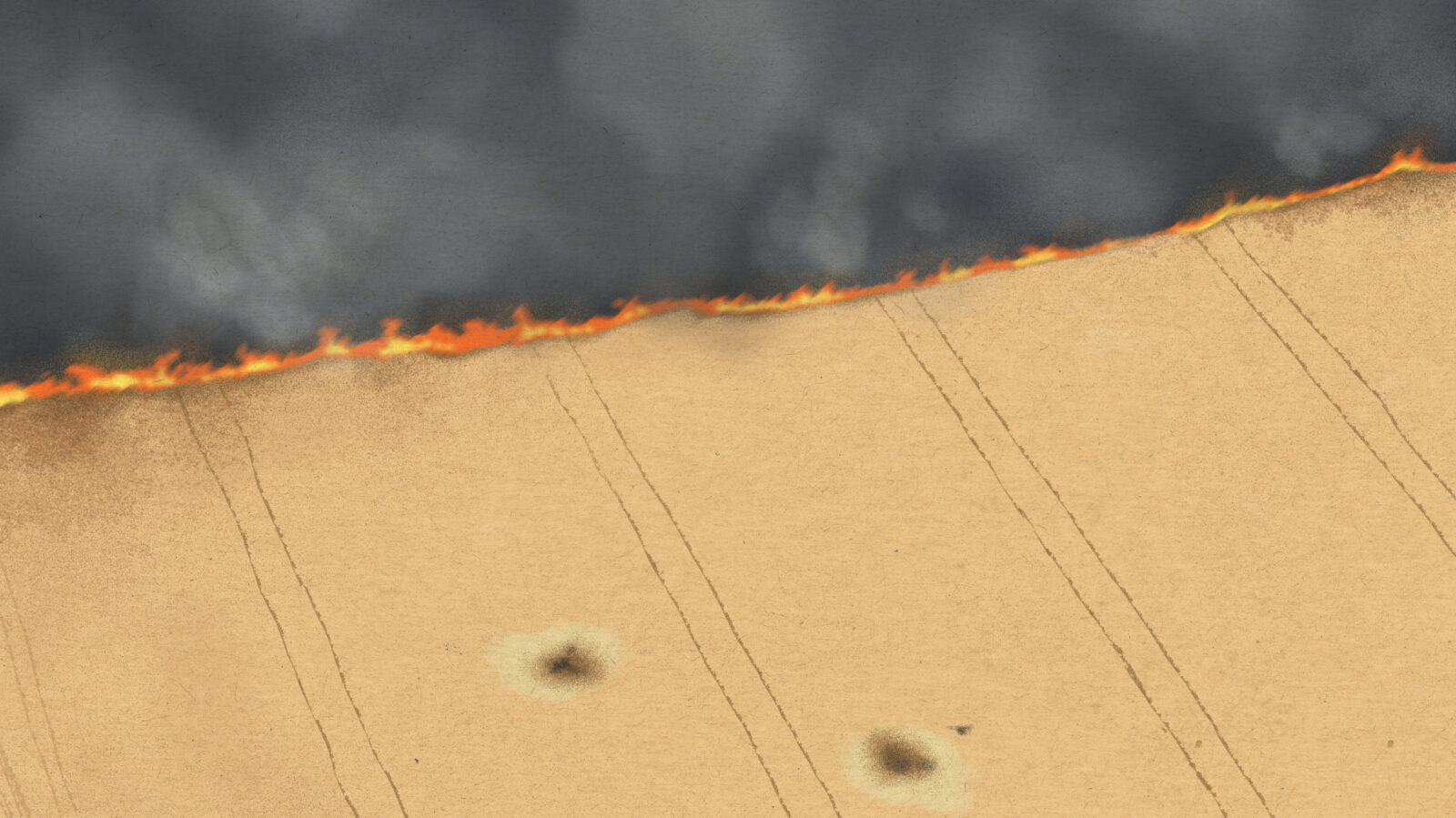

Intense rocket and air shelling targeted the Skhidnyi neighborhood, Sartana, Volnovakha, and the nearby villages. The wounded poured in from these areas, and our operating rooms were in constant operation. Some of the doctors who lived in Skhidnyi even took up residence in medical facilities to be closer to the patients.

When the russians launched an attack from Berdiansk, we realized that Mariupol was completely surrounded. Our nine-story building overlooked a military unit, and the looming threat was palpable. Tragically, a bomb struck the unit, affecting our building as well. Fearing for our safety, we sought refuge in my cousins’ house, where they had a large bomb shelter. Our nights were spent sleeping in the basement, and then I would rush to work, navigating through the chaos of war.

On March 1, the russian military shelled a nearby hospital with grenades, shattering the windows in the intensive care unit and passageways. The private sector was heavily damaged… They hit the Port City and Metro areas. We moved the wounded to the corridors, away from the windows, as the area was constantly shelled. The administration organized a water supply. There was no electricity, diesel generators were used during operations, and there were not enough doctors.

A trauma center was opened in the third hospital as part of the oncology center. There was a bomb shelter there, a so-called bunker. The room was neglected: no water, sanitary conditions, with broken beds, and cold temperatures. But it was well protected, so the children from the surgical department were placed there. Our families, mine and my cousins’, also moved there. Together we cleaned the bomb shelter.

On March 9, russian planes dropped a bomb on the maternity hospital, and we operated on the wounded. The number of injured was growing: 16, 30, 60, 80… Some were taken to a bomb shelter, with an underground hospital with a bandage room and an operating room.

In the midst of this chaos, my wife emerged as a true hero, bravely standing by my side and refusing to leave my support. Despite not being a doctor, she fearlessly assisted in medical procedures, injecting the injured and offering critical aid. Her dedication and sacrifice made a significant difference during those difficult times.

On March 13, the russians targeted the children’s oncology building, causing the stairwells to collapse. On March 16, russian aviation bombed the Drama Theater. We received the wounded. The next day, the occupiers shelled the children’s surgery with grenades, and then all those lying in the corridors were taken to the basement. This meant that the children who first came after the attack on the Drama Theater were again in danger. In the radiology department, there were fully charged guns for radiation therapy. Radiation! If a bomb had hit there, there would have been a catastrophe in the center of Mariupol.

We received wounded people from all corners of the city and provided medical care for them in the bomb shelter. Fortunately, we had an ample supply of disinfectant stored in the basement, with bottles scattered all around the shelter. However, the conditions were challenging, as there was a shortage of drinking water and no washing facilities, making it easy for intestinal infections to spread. It was too risky to venture outside for using the toilet, as many who attempted this were injured or lost their lives. To combat the risk, we diligently taught everyone to disinfect their hands at least 20 times a day.

Despite the difficulties, we managed to provide enough medicines for the wounded, and the hospitals in Mariupol were fully staffed. The local community also played a crucial role by bringing food supplies, which became the only means of sustenance in the devastated city. Even a barley package and moldy cheese were cherished like precious treasures.

Once there was a man with a severed arm. He lived in the Prymorskyi district. I vividly remember a particular incident when a man from the Prymorskyi district arrived at our shelter with a severed arm after the shelling. Thankfully, he later evacuated from Mariupol and received a prosthetic arm, and he is now doing well. At that time, though, we faced a challenging situation with limited resources, and he needed an amputation, for which we lacked the appropriate tools. I once contemplated using garden shears that we had submerged in disinfectant, but soon realized it wouldn’t be sufficient. Fortunately, we discovered a bayonet knife left behind by the russian terrorists as they vacated the shelter, which had a blade on one side and a saw on the other. With this improvised tool, we were able to perform the amputation and form a stump for him.

The memory of that knife, the one that helped save a life, remains etched in my mind. I am determined to return to that basement one day, find the knife, and hang it on my wall.

After March 15, the pediatric surgery and oncology department of the 3rd hospital fell under the control of the “105th regiment of the DPR.” They established their medical service and headquarters there. The occupying forces later visited our bomb shelter, inspecting documents and searching for police and Armed Forces of Ukraine personnel. The shelter mainly housed children, women, and wounded individuals.

The water supply was extremely limited. The occupiers took away one empty barrel, but we managed to find another one. By the end of March, there were 56 people seeking refuge in the basement. To indicate our status as a medical facility, we hung a red cross at the entrance, which deterred the DPR personnel from interfering with us since we were the sole caregivers for civilians in the city. They meticulously checked the documents of everyone seeking medical assistance.

There was no humanitarian aid being offered to us. Occasionally, we made arduous trips to Port City where humanitarian aid was being distributed. We stood in long queues in the morning, returning in the evening with loaves of bread to sustain the people in the shelter.

In April, the building was taken over by signalmen, who were Ossetians. However, they quickly fled, fearing radiation, leaving the place once again in our control.

Throughout this period, we had no direct information about the situation at the frontlines. The DPR radio broadcasted false claims that “there is no Kharkiv,” and “there is no Zaporizhzhia,” but we were listening to Ukrainian radio and knew that our men were courageously fighting back against the occupiers. We were filled with hope when we heard about the sinking of the cruiser “moscow.” Our spirits were lifted, and we anxiously waited for the day of de-occupation. Leaving the wounded behind was out of the question; we remained committed to our patients and couldn’t abandon them.

As April progressed, patients with severe injuries were evacuated to the 2nd hospital where russian medical staff were operating. Among the evacuees was a girl with an abdominal injury, which presented a challenging situation in a basement setting where we lacked specialized equipment and expertise for pediatric surgery. Additionally, there was a Roma family who had lost their home to a fire; the father and eldest son had tragically lost their lives, leaving two children and their pregnant mother behind. She had given birth on February 24 or 25 in the midst of the turmoil. Tragically, all families in the shelter had experienced loss and grief. Another pregnant woman and a young man with a fractured spine also sought refuge in the shelter, and we did our best to care for them in such difficult circumstances. When it came time for the wounded to be transported, we improvised by placing mattresses and blankets at the back of a truck to ensure some comfort during the journey.

The only dead person in our basement was a woman, Ania, with a severe head injury and a broken hip. We were devastated that we couldn’t save her. As for the numerous deaths that occurred in pediatric surgery, both adults and children, including babies, succumbed to their injuries. The morgue on the premises became overwhelmed, and bodies were left strewn on the streets after the hospital was shelled. The DPR later arrived and collected the corpses, taking them to an undisclosed location. Among those taken was Ania, whose lifeless body was also removed.

Despite the grim circumstances, Easter brought some miraculous family reunions as people found their loved ones in the bomb shelter, relieved that they had survived. One heartwarming story was of a 16-year-old boy from Skhidne who had spent his time in the hospital shelter since February 22. His father eventually found him on Easter, marking a joyous occasion amid the chaos.

For my wife and me, we were only able to return home on April 17 when the DPR and Ossetians finally vacated the hospital premises. Sadly, our apartment had been burnt down, and our two cars were looted and disassembled. It was a challenging situation as finding wheels and a functional battery in the destroyed city proved difficult. Nevertheless, we managed to get one of the cars running, using its battery to tow four cars, including ours and those of people who had been sheltering with us.

On April 26, we set out from Mariupol in our shot-up car with the windows taped over. The news about evacuation opportunities emerged later, so we had to rely on ourselves for the journey. Due to my work at the Ministry of Internal Affairs hospital, we couldn’t go to the filtration center, so we opted to travel by less-conspicuous trails. We arrived in Manhush, where we encountered a long line of thousands of cars. To ensure our safety during possible inspections, we meticulously cleared our phones, tablets, and laptops of anything that could be incriminating.

We drove to Melitopol without filtration. The car took us to the city, then stalled and did not work. We paid $500 per person for the transportation. We hoped there was less chance of exposing me at the Chonhar checkpoint. FSB officers interrogated me from 11 AM to 7 PM. They took my passport and phone, stripped me of my underwear, and searched for tattoos. They also found the number of a patient who worked for the Ukrainian army, and asked a lot of questions. They forced me to sign papers that I would not work for Ukrainian or foreign reconnaissance, and let me go.

We traveled through the temporarily occupied Simferopol and then crossed russia to reach the border with Latvia. We experienced a delay at the Ubylinki checkpoint from 4:30 to 9, but thankfully, our migration cards filled out in Crimea helped ease the process. Arriving in Latvia brought a sense of relief and freedom. From there, we continued our journey to Poland, where we have some plans ahead. Our experiences have been challenging, and we hope for a brighter future. After everything we’ve been through, the children know who to hate – those who did this to their city and country, which means all russians.