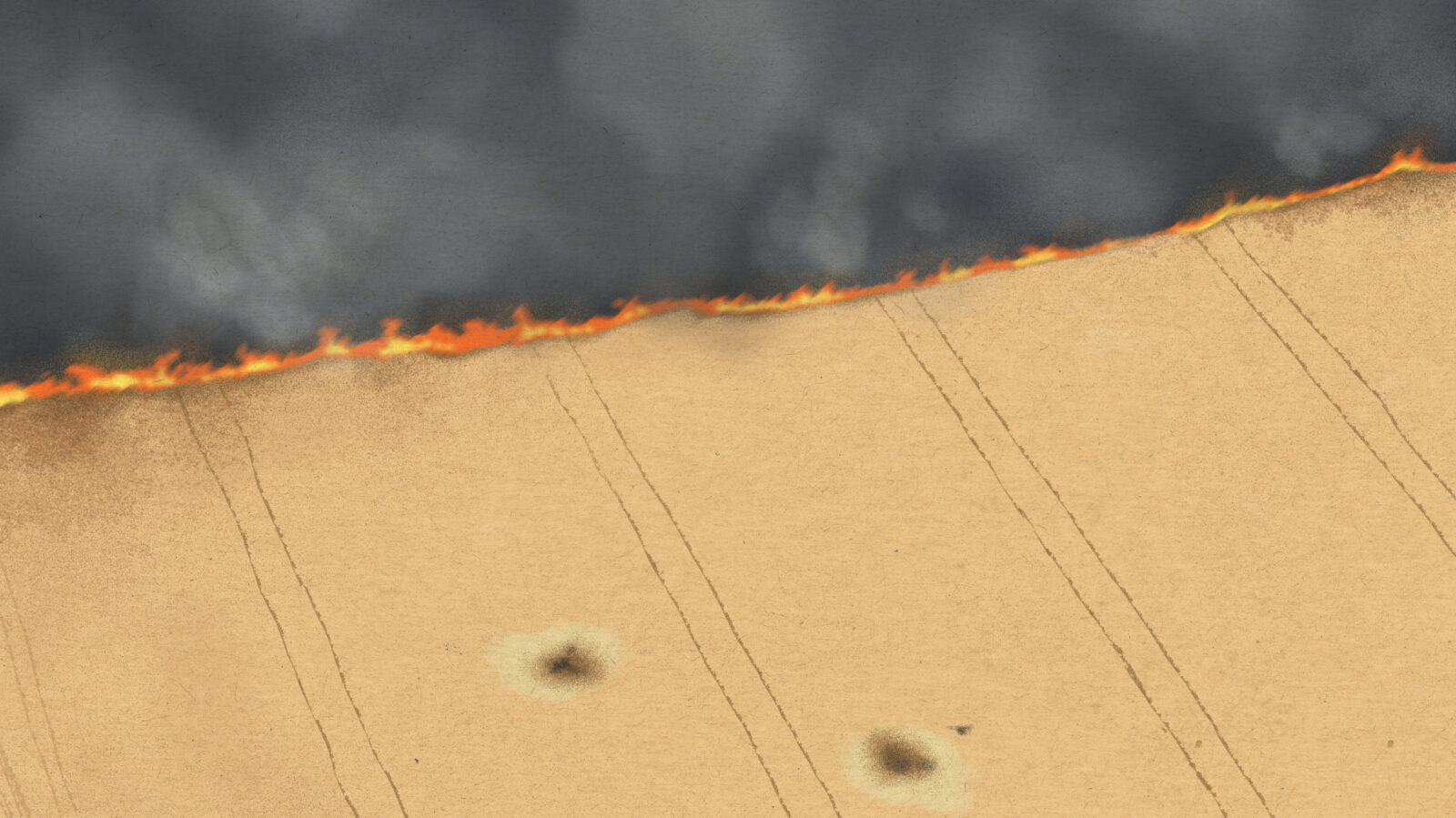

Illustrated by Tanya Guschina

The Russian troops have been shelling my hometown, Severodonetsk, since the beginning of March, every day. Volodymyr, my stepfather, is 64. He wasn’t accepted to the local defense units, he had nothing to do in the city but did not want to leave. By coincidence, mom was just visiting me a day before the war. So we were trying to convince him to leave, too, but he wasn’t bulging.

On March 8, an explosion destroyed all the windows on their balcony. But already an hour after that, he felt relatively safe (it was only a balcony after all) and still refused to leave.

March 13 became a turning point. That day he was doing his morning exercises in the living room. At this moment he heard, or felt, an explosion. He reacted immediately: fell on the floor and crawled to the corridor behind two walls. When it got quieter, he was able to get up and see what happened. The windows in the bedroom were shattered, my mom’s orchids were cut short by glass fragments, and two metal shell fragments have fallen on the bed where he could have been sleeping. The fragments were hot, the synthetic blanket stuck to them.

That time, while he was shocked, it was the right moment to finally convince him to flee. But he didn’t have a car. Getting from the house to a spot where evacuation buses were expected to wait takes around 20 minutes on foot. Too long. I started calling all the local drivers, and finally one of them picked up and said, “I’ve just come back from that area, and I’m not going there until it’s quiet!” The shelling was going on and on.

A 20-minute walk (race) across a city shelled by heavy artillery is something close to suicide, I thought. Staying in the apartment seemed safer. On the other hand, evacuation buses wouldn’t wait until the evening, and the apartment is safe until it’s hit directly. While I was considering these options, my stepfather was covering a broken bedroom window with a blanket (at least some protection from snow and looters). Then he grabbed a small bag, went downstairs and headed to the Culture Palace where the buses were waiting.

Hundreds of desperate civilians were waiting there—way more than the buses could accommodate. The priority was women, children, and the elderly, so my stepfather waited in the crowd for an hour, and another hour while the artillery continued its work—luckily, a different area was the target.

The first batch of buses left fully packed, the drivers promised they would come back, but who could know for sure. It looked like he would have to go back home. And maybe he would not be as brave the next day to take another 20-minute trip.

Suddenly a minibus stopped by, a cargo one. “Get in, quick,” shouted the driver, who was wearing a khaki outfit with stripes along the sides. People hesitated (“Who is he? Is it safe?”) but finally got on. The bus drove off. There were no seats. An elderly woman lied on the floor, some tried to sit on a spare wheel on the floor, the rest struggled to stay in a vertical position. There were no windows, so they couldn’t see the road. I think they prayed all the way.

Apparently the driver was one of the volunteers helping people to get out of town. He delivered people to the center of a neighboring town, Lysychansk, and from there they managed to get on a bus that took them to a train platform. A few hours later they changed to another train, and after 30 hours they reached Lviv.

It’s a sheer accident that Volodymyr could safely make this long journey. Some of those who managed to get into a proper bus arrived late for the train because their driver got lost. Others were not able to fit into the overcrowded train heading to Lviv.

The 1,500 evacuated passengers had no idea what city the train was heading for up until they arrived. It was enough to know it was going west.