Author: Oleksandr Vasylenko

Illustrator: Olha Panteleimonchuk

Yuliia Bondar resided in Mariupol with her mother and a 9-year-old son on Myr Avenue while working as a trolley bus driver. During the quarantine, she brought her son to her workplace to facilitate his online studies, never anticipating the difficult challenges that lay ahead.

Since 2014, the Vostok SOS Charitable Foundation has been diligently gathering information about Russian war crimes, aiming to uphold justice and the right to truth. The account featured in the publication “War. Stories from Ukraine” was recorded by Tetiana Petrova and penned by Oleksandr Vasylenko.

On February 23, the realization of the imminent threat of a full-scale war struck me. A friend, whose brother served in the “dnr,” informed me that an attack on Mariupol was planned for the morning. However, on February 24, I went to work. Though I heard explosions throughout the day, I had grown accustomed to them over the course of the eight-year war. As I reached the Illichivsk market, the sounds intensified, and I witnessed long queues forming across the city as people withdrew cash or purchased food.

After work, I visited the store, maintaining a calm demeanor. I stocked up on long-lasting food items like pasta, cereals, and canned goods. Additionally, I filled containers with water, including the bathroom, as a precautionary measure. Later, I decided to prepare a sleeping area in the basement. The first night, we slept at home, but the following day, my son and I sought refuge in the basement.

On February 24, Mariupol experienced a blackout as street lights were switched off. In the evening, I encountered two men at the bus stop, likely police officers. Seeking guidance, I asked them about necessary precautions and how to behave on the streets during moments of danger. One of them offered advice that proved invaluable — he said, “If you’re walking down the street, don’t stop.”

During February, we still had access to the network, allowing us to stay updated with news from the government-controlled territory. However, when the shelling commenced, all communication was cut off. The russians had imposed a complete information blockade, but we occasionally managed to catch snippets of information through the radio.

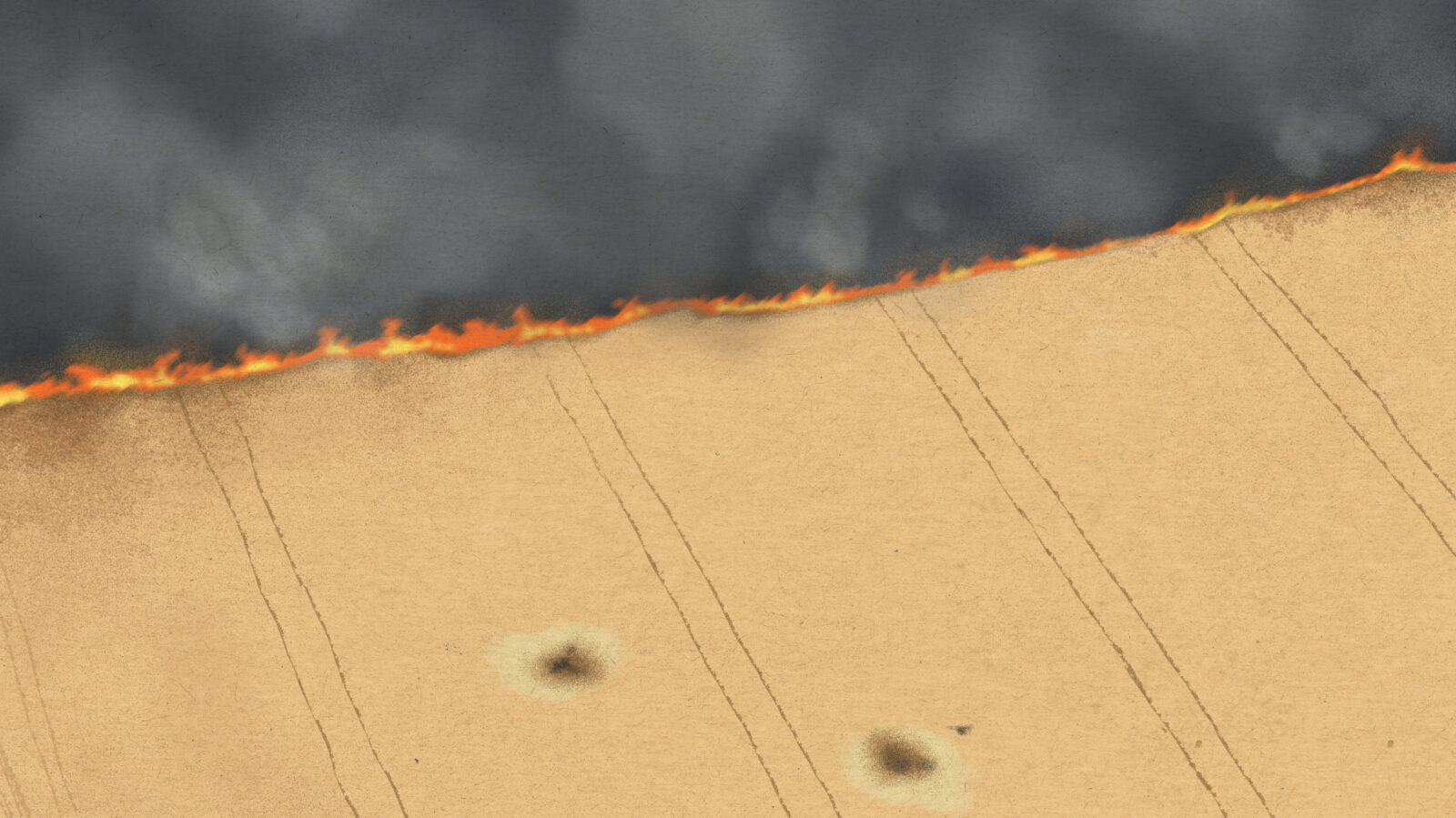

From the beginning of March, planes began flying over the city, dropping bombs as they approached from the direction of Eisk (russia). Following March 1, the blackout intensified. While my son and I spent our days in the basement, my mother refused to join us there.

The explosions grew alarmingly close, and one morning we were jolted awake by a blast that struck the building across the street — a nine-story structure.

On March 5, seeking a safer environment, my brother took my son and me to his residence, a private house in the center of the city. The atmosphere there was noticeably quieter. However, my mother adamantly refused to leave her home and remained behind. I occasionally visited her, witnessing the devastation along the way — burned houses and lifeless bodies. Initially, the authorities would remove the deceased, but as the situation worsened, the bodies were left lying by the roadside.

March 11 brought another harrowing experience. Upon arriving at my mother’s house, I discovered it engulfed in flames. Just recently, people had been nearby, cooking their meals over an open fire. But that day, there was no one. Frantically, I rushed to the apartment, finding the door ajar. Blood stained the walls, everything was shattered, and my mother was nowhere to be found. We had a cat as well, and I called for him, but he failed to emerge.

In a state of panic, I darted outside and entered various basements, desperately shouting my mother’s surname. The basements were overcrowded, and I wasn’t always allowed entry. Finally, in one basement, my mother’s weak voice reached my ears. Her face was covered in blood, and her arm was broken.

I swiftly took my mother to Children’s Hospital №3. Disturbingly, the doctors complained about the lack of space to store bodies, and the basement was already teeming with people. Some lay dying on the floor. We spent several hours there, and eventually, my mother received a cast for her injured arm. Afterwards, we made our way to my brother’s place.

The following day, I found our cat inside my flat. Scooping him up, I hurried towards the door, but the shelling commenced, forcing us to seek refuge once again in the basement.

Within a week, I made the decision to leave Mariupol with my son and cat. Initially, my brother drove us to Port City, where we managed to find transportation to Nikolske. In Nikolske, I noticed a few buses with russian registration plates, but I had no intentions of heading to russia. My goal was to find a bus to Zaporizhzhia, but my attempts proved unsuccessful. Consequently, my son and I spent the night at a school, along with others who were unable to depart as planned.

While at the school, I encountered two people from Kyiv who had come to pick up their mother. As they were unable to enter Mariupol, they also remained at the school. I assisted them in finding a blanket and a place to sleep, and suggested that we travel to Zaporizhzhia together. They agreed, and the following day, we embarked on our journey. We encountered various checkpoints along the way, encountering russians, kadyrovites, buriats, and others. Their eyes held a hunger for taking things, mostly cigarettes. When we ran out of cigarettes, they even took our food.

Our hearts filled with joy when we finally encountered our defenders and embraced them. From there, we headed west in Ukraine, and eventually, my mother joined us there. Subsequently, I crossed paths with a volunteer from the UK who I could easily communicate with due to my proficiency in English. He offered to take us to Slovakia.

Recalling life in besieged Mariupol is a challenging task. Initially, I feared the russian planes, awakening to the jarring explosions of bombs. The fear was overwhelming, realizing that the next bomb could strike us. Gradually, the fear diminished, replaced by a sense of impending doom.

Witnessing so much death, I ceased fearing it. As I gazed upon the deceased, I contemplated the suffering they endured, uncertain of the torment that awaited me.

In Slovakia, my son and I sought the assistance of a psychologist. She reassured us that my son was coping well. He often depicted tanks, blood, and death in his drawings, speaking of the Azov regiment fighting against the Nazis and emerging victorious. The expert explained that these drawings symbolized the triumph of good over evil, alleviating any concerns. He expressed what he had experienced and eagerly awaited Ukraine’s victory.

The day of victory will undoubtedly mark the most significant and joyous moment in my life. We hold steadfast belief in our soldiers and envision a peaceful future for our free nation.