Illustrated by Tanya Guschina

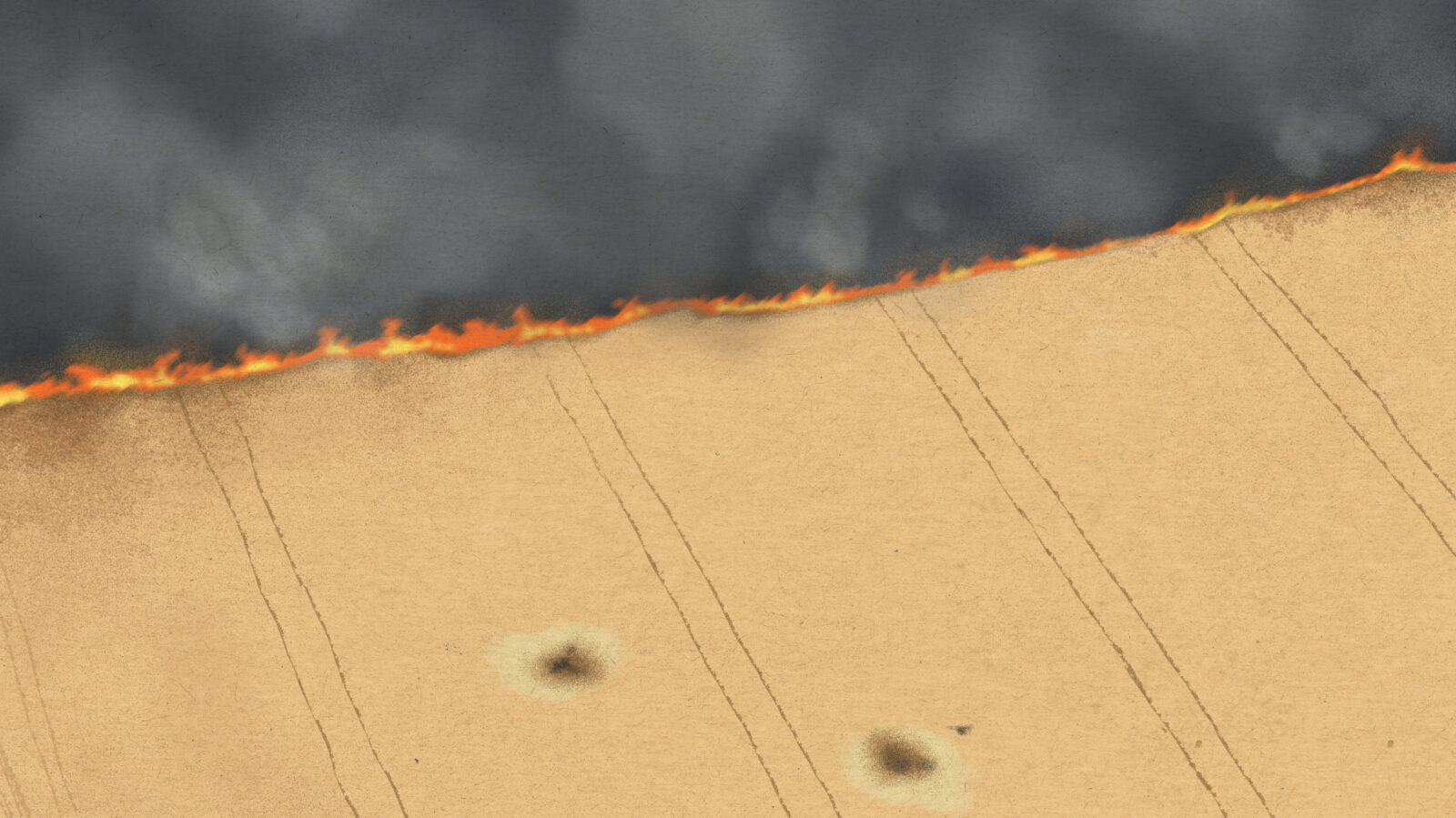

For over 4 months, Ukraine has been fighting for its survival against a neighboring state. Russia launches dozens of missiles at Ukraine every day, bombs peaceful cities, ruins infrastructure and destroys everything on its path. Over 20% of Ukraine is now under occupation, thousands of people have died, and millions have been forced to leave their homes, loved ones, and sometimes their life’s work.

There is no reliable data on how many businesses have ceased operations due to the war. According to the findings of a survey by the Ukrainian Ministry of Digital Policy, as of June, 46.8% of enterprises are still on pause or barely working due to the full-scale Russian invasion. And according to a study by Keep Going, 40% of small businesses are currently in the warzone, and only 16% of the respondents have moved to other regions. Most business owners have to start everything from scratch and set up the processes anew. And they have to believe that their business won’t be destroyed by Russia again if it launches more missiles.

We’ve collected three stories of small Ukrainian businesses from the Kyiv Region, Mariupol, and Berdyansk. The latter two cities are currently occupied by Russia. One of the businesses has survived the occupation and kept afloat. Another one has been destroyed by the Russians and launched from scratch in another city. The third one is suspended completely, awaiting deoccupation.

BorodyankaKhlib: a business which survived the occupation by miracle and fed people in an occupied city

“The bakery that survived.” That’s what Viktor Tkachov, the owner of a small bakery called BorodyankaKhlib, now calls his business. When the Kyiv Region was under occupation, his workers were the only ones in the area who continued to cook hot food. They did not stop working and, under shelling, kept on baking fresh bread for people in neighboring villages and towns.

Viktor bought a bakery in the village of Klavdievo-Tarasovo near Borodyanka a year ago, after his restaurant in Dnipro burned down. He created a business plan, found new clients and rescued the business which was on the brink of shutdown. The baked bread was delivered to Kyiv and sold in the neighboring localities.

On February 24, after waking up from explosions in Kyiv, Viktor instantly thought about the bakery: what would happen to it, to its workers, and to the bread?

“My phone was ringing constantly. Big manufacturers immediately stopped delivering bread to this part of the Kyiv Region, because it became dangerous to drive in the direction of Bucha and Irpin. The owners of local stores found my phone somewhere and asked if they could buy some bread. Together with my workers, we decided to continue working and adjusted our schedule. Before, we used to bake at night to deliver fresh hot bread in the morning. Now we switched to day shifts: our people were scared of working at night, and it no longer mattered to the customers when the bread was baked. As long as it’s there,” says Viktor Tkachov.

The local government and the Territorial Defense (a separate division in the Armed Forces of Ukraine) quickly learned about the bakery which became the only source of bread for the entire district. The military brought diesel fuel and a power generator to the bakers, in case the power was cut off. The next day, the gas station burned up from shelling, and the power was indeed cut off. The village found itself under Russian occupation on the very first days.

“We got 8 tonnes of flour from a nearby food warehouse. Its owners left the Kyiv Region on the very first day, but they allowed us to cut the locks off and take all the food we needed. That way, we miraculously ended up prepared for a month-long occupation,” says Viktor.

The bakery gave some of the bread free of charge to hospitals, elderly people, and the military. The rest was sold directly to locals for prewar prices.

“People stood in line, and we sold half a loaf to each, so that there’s enough for everyone. Our bakery workers sold it themselves: one day they baked bread, the next day they sold it, and the third day they took a break,” recalls Viktor.

Resellers tried to make a deal with him to sell the bread for three times the price. Viktor didn’t make any deals with these looters.

“They said, just open the gate, we’ll load all the bread and pay you right there. But I’m proud that I did not hesitate for a second,” shares Viktor.

For a month, his bakery was essentially the only place to buy bread. Stores were closed, markets weren’t working, humanitarian aid wasn’t reaching them. Without gas or power, people cooked outside on open fire—from the stocks they still had left. So the opportunity to buy half a loaf of fresh bread felt like a miracle.

Through volunteers from Zhytomyr who delivered medicine to the occupied Kyiv Region, Viktor passed on dry yeast to the bakery. Connection with the workers was very sporadic.

“To contact me, they walked out to the field where there was some connection at least. We called each other once or twice a week. I said goodbye to my bakery many times, and I was prepared to hear next time that it no longer existed—that it was destroyed by an explosion, or robbed by the Russians,” says the entrepreneur.

He was able to come to his bakery in early April, as soon as the Kyiv Region was liberated from the occupiers. He brought his workers a truckful of food, cigarettes, sweets, and a big cake.

It felt like they gave their hundred percent during the occupation, and when it was all over, they fell into an emotional hole. I think the war has left a trace on them for their entire lives,” Viktor says.

For another month, until the power was restored, the bakery worked on a generator.

Now the work has resumed in full. Although now, over 90% of the bread is sent to the neighboring villages and towns instead of Kyiv—in those towns, the Russians have burned or looted most big supermarkets. While they are rebuilding, only small local stores are working. Some vendors sell food right from their trucks.

Viktor is convinced: under the conditions when many major Ukrainian industry giants have been destroyed by the war, small businesses can support the economy and manufacture goods which will be in shortage from now on. He is now looking for a business partner to increase the production volume. Because big chain stores still don’t work in the Kyiv Region, and major suppliers don’t bring bread to small stores. But everyone needs bread.

First One on Coal: how to start everything from scratch when your business is destroyed

Maksym Pustakov from Mariupol (Donetsk Region) had an alarm set for 6 a.m. on February 24: he needed to go to Slovyansk to open the sixth restaurant of his chain called the First One on Coal. The rented rooms had already been renovated, the equipment and supplies had been purchased, the team had been hired—everything cost about $15,000. But Maksym woke up an hour earlier, at 5 a.m. His mom called to say that the war had started.

Maksym opened his first shawarma restaurant in Mariupol in 2020. His selling point was a special grill created by a whole team of people according to their own blueprints. The restaurant was different from regular fast food: it was a stylish cafe with an open kitchen where all the health standards were followed. Customers liked it, and within a year and a half the business grew into a chain of 5 restaurants.

The team of the First One on Coal in Mariupol

Maksym had a clearly thought-through plan for scaling up. Back in December, he already knew in which cities in the Donetsk Region he was going to open new restaurants. While the media was discussing the possible full-scale Russian invasion, his team was renting rooms and buying equipment. In addition to the restaurant in Slovyansk, which had been fully prepared for opening, he also had a half-prepared cafe in Kramatorsk.

All these 8 years since the war began, we lived in Mariupol and saw the city developing despite its proximity to the temporarily occupied territories. So we didn’t believe that a full-scale invasion would start in Mariupol. When you see an entire university built right in front of your eyes, you believe in your city’s future and stay calm. I was growing my business, I had no time to be scared,” says Maksym.

He spent the first day of the full-scale Russian invasion suspending food deliveries, conserving his restaurants, taking small equipment out, and thinking how to transport at least a part of the business out. At the same time, Maksym had to take care of his family, his four-year-old son, wife, and parents. Traveling out of Mariupol was already scary on February 25: the Russians started surrounding and bombing the city.

He stayed in Mariupol with his family until mid-March—without cell connection, water, power, or gas. All this time, his family lived in shelters—under their own house, at their friends’ and relatives’. The Russians kept bombing the city ceaselessly, flooding it with missiles. Maksym’s restaurants on the outskirts were destroyed. The restaurants closer to the city center were ransacked by people in search of food. There was already a famine in the city. His grills were taken to people’s yards to cook on them. Almost from the first days of the full-scale war, stores stopped working in Mariupol, people melted snow to get water, and survived on their stocks of cereal and pasta. It was impossible to buy food or medicine.

Maksym and his family managed to leave the city on March 16, through the first “green corridors.” He could not take any equipment with him, they only took the necessities. Maksym’s apartment had already been half-destroyed by that time, and the homes of his parents and his wife’s parents had burned down completely.

Maksym and his family first traveled to Zaporizhia, then stayed with some friends in Kropyvnytskyi. In late April, they moved to the capital, and three weeks later they found a place in a residential neighborhood to open a new restaurant there—in the same format as in Mariupol. Maksym says: “I still have the fear of losing my business. We probably won’t be able to restore it for the second time.”

The restaurant before and after the Russian invasion

The first customers of the business that rose from the ashes were people displaced from Mariupol. They came to taste the familiar shawarma they were used to. It reminded them of their home, which was razed to the ground by the Russians. The restaurant now employs three people: Maksym himself buys supplies and manages organizational issues, his wife runs the cash desk, and the shawarma is cooked by a chef who also successfully left Mariupol for Kyiv. Maksym dreams of restoring his chain—not just in Kyiv, but all over Ukraine. At least in the cities where his team members have moved to.

Mariupol, where Maksym’s restaurant chain was located, is now occupied by the Russians and almost completely destroyed by fighting. According to different estimates, around 22,000 civilians have been killed there—some by Russian missile strikes, shelling and bullets, and some due to the lack of medical care and food. Slovyansk and Kramatorsk, where Maksym was planning to open new cafes, are now on the frontline: the Russian military is trying to capture them and constantly bombing them.

Formaggio_olive: a cheese dairy waiting for deoccupation

“I’ve been offered to work as a cheesemaker in Poland, the UK, and Germany, or to open my business from scratch in the Khmelnytsky Region. But I can’t think about it, I’m waiting for my native Berdyansk to be de-occupied, and for us to return home to make cheese,” says Aliona Lubenska. For the past 8 years, her husband Yuriy and she were making craft cheese in Berdyansk (Zaporizhia Region), and they were forced to abandon their life’s work. Their city has been occupied by the Russians.

Aliona and Yuriy cherished and loved their business. They started with cheese experiments in their own apartment. Soon they bought a house, turned it into a cheese dairy, and brought a handmade tank from Italy. They made 15 kilograms of cheese per day in the 150-liter tank. Their menu included up to 15 kinds of craft cheese which they sold to the locals or on their Instagram page. Thanks to their devotion and love for their work, the cheesemaker family from Berdyansk quickly became famous.

On February 24, Aliona woke up at 4 a.m., went to see her younger daughter Aurora, pulled her blanket up, walked around the house, drank some water. And then she heard explosions. A Russian missile hit a military base nearby. Aliona and Yuriy wrapped their daughter in a blanket and went downstairs to the cellar.

“We didn’t plan to move anything out or run anywhere. We had 600-700 kilos of aging cheese in the cellar. It needed special conditions, you can’t transport it in a regular truck. And I couldn’t even imagine how we would move the huge tank,” recalls Aliona.

Berdyansk was occupied already on February 27. Most of Zaporizhia Region was also captured by the Russian military. But even then, Aliona’s family did not want to move. They participated in pro-Ukrainian rallies and continued buying milk and making cheese.

“The farm still had to milk the cows and feed them something, so we kept buying 60 liters of milk per day. But people quickly started running out of money, and more and more often, we did not sell the cheese but gave it out for free. We pasteurized milk and treated people to it, ran cream through the separator, boiled water in the oven and gave it out to our neighbors. Gas had already been cut off by then. There was so much work,” says Aliona.

They delivered cheese to schools where people evacuated from Mariupol were staying. Although Berdyansk was under occupation, people from Mariupol were arriving there, because 90% of their city had already been destroyed by the Russians by then.

“Our street is close to the Mariupol-Bediansk highway. Convoys of shot-through cars with Mariupol residents were driving on it. People would come out of their houses and take these people in. We did the same,” says Aliona. “The thought of leaving Berdyansk did not even cross our minds. We felt so useful: in the morning we delivered cheese, in the afternoon we attended pro-Ukrainian rallies and streamed them on social media. Back then we felt like the Russians were afraid of us and that we were the ones making decisions here. It soon became clear that they just hadn’t received the order to disperse us yet.”

On March 18, the Russians detained the activists after another rally. Everyone who came out to express their position was threatened with being shot. The Lubensky family could no longer buy milk—the milk truck from Prymorsk was not allowed to pass through checkpoints. And they no longer had the money to buy it either—the family was running out of savings.

Aliona started receiving threats: “Aliona, the Kadyrovists are already in the city, you know what they’re going to do to you and your Aurora.” There were more and more messages of this kind, and they included the full address of the cheese dairy with threats that someone was going to come for them soon.

The family gave their last 100 kilos of cheese to volunteers who were welcoming the evacuated Mariupol residents. Each car received a piece of cheese and a loaf of bread, so that the people could at least eat something and drive on.

On March 21, the family couldn’t stand it anymore and left Berdyansk. They left a family from Mariupol in their house. In the Khmelnytsky Region, where the family moved to, they were offered to set up a cheese dairy in partnership. The business was about to open, but Aliona changed her mind at the last moment.

“People kept writing to us on social media asking for help. Our customers from Irpin, Bucha, Mariupol kept asking for things, food, baby food, diapers. I started posting about donating things, we received parcels, we gave them to whoever needed them. And when we found out that the Kyiv Region had been unoccupied, we rented a van, bought some things and food for our own money, and went there. One trip determined everything. I came back and told my potential partners that I couldn’t think about business now. Now we are needed elsewhere, and cheese can wait a bit.”

Now Aliona and Yuriy are not making cheese. They’re renting a one-bedroom apartment in Kyiv and drive around the Kyiv Region almost every other day, delivering aid. They make their living by selling video recipes for cheese, starters and ferments.

Tens of thousands of people have now become volunteers in Ukraine, buying equipment for the army to bring the victory closer, helping displaced people, rescuing animals from combat zones, and supporting people from the de-occupied areas who have lost everything. Businesses across the country have reoriented: instead of making money, they volunteer for those who have lost everything.

“I went to Germany for a week, to a farm where I was offered a cheesemaker job. But I realized that I could not be outside Ukraine. I want to be in the midst of the events and welcome the victory here, at home. I hope Berdyansk is liberated soon, and we will go home to cook our cheese. My husband and I used to travel around Europe a lot and dreamt of moving there: we were charmed by European cheese dairies, and we felt like everything there was right for doing business. But now we don’t want to go anywhere anymore. We only want to come back home.”

Aliona’s house in Berdyansk is still intact—at least that’s what her neighbors say. The city is still under occupation, the Russians have imposed their rule on it, there are no jobs, children have not attended schools or kindergartens since February, and many people can’t even afford to buy food.

We constantly read that our friends go missing, people who have stayed in the city to volunteer. A friend of ours joined the ambulance service to help people, he was arrested, and he’s been held captive for 2 months, nobody knows what has happened to him or if he’s even alive,” says Aliona.

She believes in victory and waits for it—even if nothing is left of her house in Berdyansk.

“Well, then we’ll go to clear the rubble. Nothing will happen to the cellar, that’s for sure, and the cellar is all we need to make cheese,” says Aliona. “We will do everything to bring life back to Berdyansk. Because if we all leave our cities and our country, then what are our guys and girls dying for right now?”

***

Before the war, over a half of Ukraine’s GDP was, directly or indirectly, produced by small and medium-sized businesses. According to experts from Advanter Group, direct losses of small and medium-sized businesses in Ukraine since the beginning of the full-scale Russian invasion are estimated at $64-85 billion. Decades may be needed to rebuild completely and compensate for these losses.

The project is produced with the support of Lviv Media Forum and EU-funded programme House of Europe.

Writer: Tetiana Honchenko

Editor: Alyona Vyshnytska

Illustrator: Tanya Guschina

Translator: Roksolana Mashkova