Author: Natalia Kaplun

Illustrator: Nataliia Shevchenko

Anastasia Fomenko (name changed for security reasons) was a resident of Mariupol, where she was born and raised. She worked as a secretary in one of the departments at the Mariupol port and shared her life with her boyfriend in the Skhidnyi neighborhood.

Since 2014, the Vostok SOS Charitable Foundation has been documenting war crimes committed by representatives of the russian federation, aiming to ensure justice and the right to truth.

This story was recorded by the Foundation’s dedicated documenters, Maria Biliakova, and Natalia Kaplun. The author of this text is Natalia Kaplun for the publication “War. Stories from Ukraine”.

On February 24, 2022, I was abruptly awakened at four in the morning by nearby explosions of immense power. The force was so intense that it blew our doors off their hinges. Despite the chaos unfolding around us, I gathered myself and proceeded to go to work at the port later that day. Explosions continued to echo through the air, causing chaos and urgent meetings. Soon, news reached us that russian ships had approached the port, and we were allowed to go home. As I boarded the minibus, the atmosphere was tense, and the hurried pace mirrored the anxiety that gripped everyone. People lined up at ATMs and stocked up on food, uncertain of what the future held.

Meanwhile, my boyfriend was walking along Skhidnyi and witnessed a devastating strike in a residential area. The impact was so powerful that he was knocked to the ground, while civilian vehicles erupted in flames within the yards. Realizing the gravity of the situation, we made the decision to relocate to the 23rd micro-district, where my mother, stepfather, and grandparents resided.

Although it was comparatively calmer there, a pervasive sense of insecurity hung in the air. In early March, the utilities began to fail, starting with the electricity, followed by the water and gas supply. Cooking became a challenge, and we resorted to preparing meals over an open fire in our yard.

Given that my stepfather and grandfather had disabilities, my boyfriend and I took on the responsibility of sourcing drinking water and food.

However, the available supplies dwindled rapidly.

We went to the open shops, desperately searching for anything edible. Fortunately, our area had a good number of grocery stores and warehouses, granting us some luck in securing essential provisions.

But after March 8, the russian military intensified their bombardment of our neighborhood. An ominous aircraft circled incessantly above our houses, casting a pall of fear over us all. Despite the risks, we made the difficult decision not to seek refuge in the basement, as my grandfather’s limited mobility made it impractical for us to navigate the stairs quickly. Additionally, we feared that taking shelter in the basement would only increase the likelihood of being trapped beneath the rubble if our house was targeted by the russians.

One fateful night, darkness was suddenly shattered by an intense brightness, transforming the nocturnal scene into an illusion of daylight. The deafening sound of planes was accompanied by the horrifying sight of bombs raining on two nearby houses. To my disbelief, one of those houses stood perilously close to our own, while the other was situated in the vicinity of my school, School 67. The shockwaves from the explosions shattered our windows. The neighboring building bore the brunt of the devastation, with seven apartments lost. The house near the school was once a place where people lived and thrived.

The residential area we called home bore witness to more than just the aerial assault. House No. 4 on Hrushevskoho Street was subjected to intense shelling, distinct from the bomb attacks. I recall the heart-wrenching sight of a wounded man being rescued from the building.

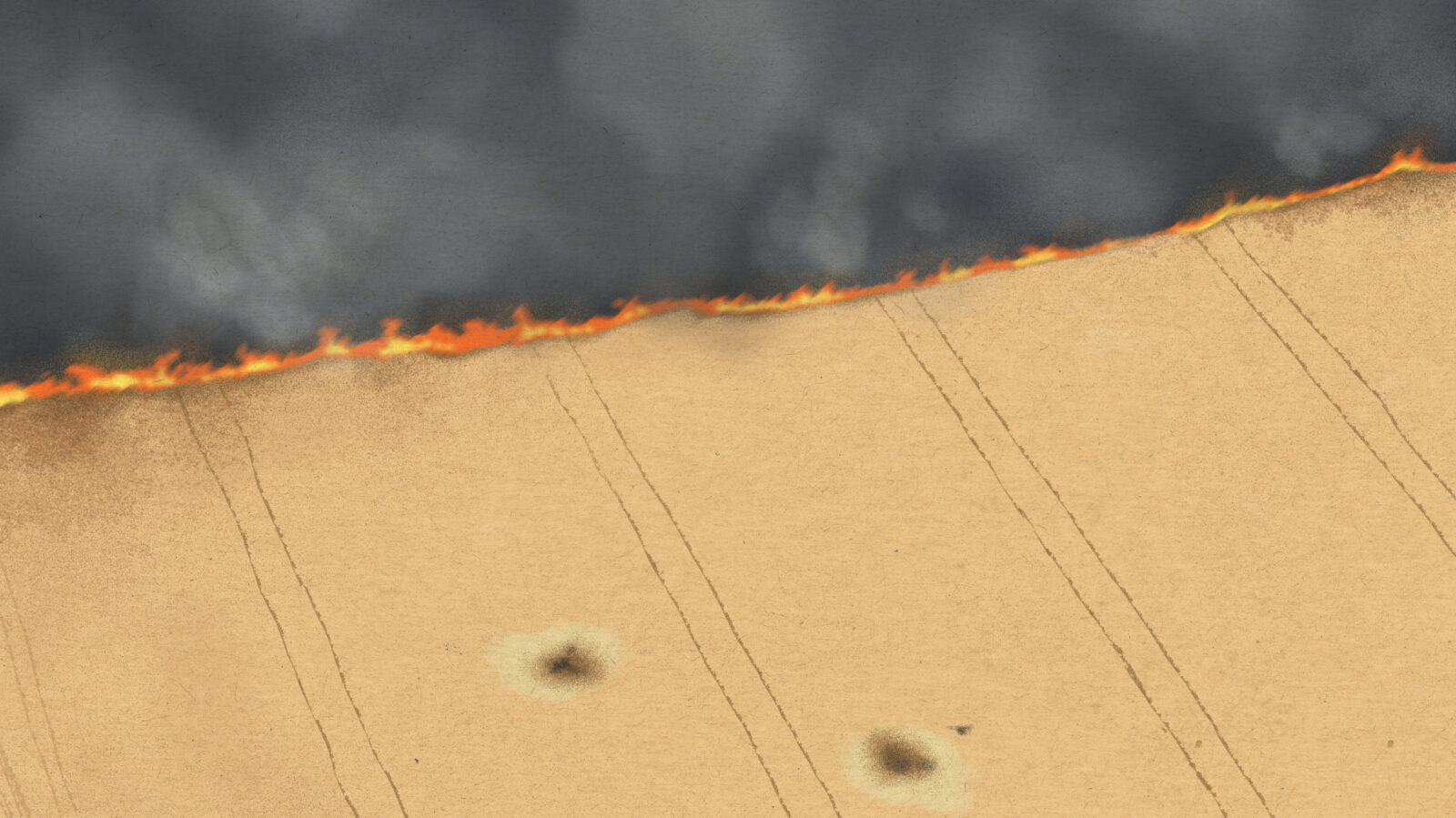

Venturing out searching for water and food became an increasingly difficult endeavor. Despite the risks, my boyfriend and I mustered the courage to make our way to PortCity – it was heavily shelled, and it burned down completely. The destruction was so severe that the area had been engulfed in flames, leaving nothing but ashes in its wake. Houses near the Alaska restaurant now stood as stark reminders of the havoc wreaked by the violence.

As we made our way back from the warehouses with much-needed supplies the shelling commenced, and the echoes of explosions filled the air. In a moment of sheer terror, a shell detonated dangerously close to our location. Fear gripped us, and instinct kicked in as we frantically sought refuge behind a small shop.

Around March 13, our worst fears materialized as tanks bearing the ominous letter “Z” rolled into our yard, marking the arrival of the occupying forces. The residents of the yard shouted for the tanks to depart. However, instead of heeding the pleas of the distressed community, the occupiers responded with menacing gestures and brandished their weapons. Their intentions became clear as they made threatening gestures towards confiscating everyone’s phones. Shockingly, one of the tanks deliberately ran over someone’s car.

The tanks unleashed firepower on the school building, firing multiple rounds. Not content with their assault on the school, the occupiers also targeted one of the garages in close proximity to our surroundings. It was heart-wrenching to witness these acts of aggression, especially since there were no Ukrainian soldiers present either in the school or the neighboring yards.

Between March 13 and 17, our yard and the surrounding houses became targets of relentless shelling. It was a different form of attack, not airstrikes from above, but rather a barrage of mortar fire or similar weaponry. The impact of these explosions ignited ferocious fires. here were two hits to our house — the house shook. Panic set in as flames erupted. In a desperate race against time, we rallied to extinguish the inferno, even though the absence of water posed a significant challenge. Amidst this harrowing ordeal, the russians fired upon us. Tragically, a woman in our building lost her life. She had lived alone on the eighth or ninth floor, and her daughters had moved to Italy before the invasion. The woman was burned alive.

Around March 17, so-called dnr soldiers went around the neighboring houses. Their purpose was to carry out thorough checks and verify the identities of the residents.

On March 21, we left Mariupol. The day prior, my mother and stepfather had a conversation with one of the occupiers, who made it clear that staying in Mariupol was no longer safe, and that it was necessary for everyone to evacuate. The next day we all went to Nikopolske.

We were placed in a school and stayed there until March 24. There were about a hundred people there, sleeping in the gym on the floor, there were no equipped beds. Meals were provided once a day, consisting of meager portions of pasta, some meat, and tea. The children were fortunate enough to receive two meals a day. The overall atmosphere was marred by a pervasive stench. Concerns for our grandfather weighed heavily on us. Given his frailty and limited mobility, we feared he would suffer from the cold and discomfort of the hard floor. So we opted to place him on the windowsill.

However, our actions were met with a strict prohibition, with staff forbidding us from utilizing the windowsill as a sleeping spot.

On March 25, we arrived in Donetsk, as returning to Mariupol was no longer an option. Our decision to head to Donetsk stemmed from having relatives residing there. The local authorities arranged for our accommodation in a school within the city. While the food provided was relatively better than before, there were concerns about the canteen workers. They handled food with their bare hands, which lead to health risks.

Tragically, our fears materialized as a rotavirus outbreak struck, affecting 15 individuals, including myself. The severity of the illness prompted the intervention of medical professionals who administered necessary injections and treatments. Given the disabilities of my stepfather and grandfather, we implored the authorities to expedite the filtration process.

During the filtration process, we were subjected to various procedures. Our fingerprints were taken, photographs were captured from all angles, and a barrage of questions was directed our way. It was a disconcerting experience, exacerbated by the fact that my boyfriend was subjected to a thorough inspection, with authorities examining his tattoos. Additionally, I was questioned about my knowledge of military personnel and my whereabouts in 2014, which struck me as peculiar since I was only 15 years old at that time.

They checked my phone for about 5 minutes but we cleaned everything, so nothing was there. Afterward, they gave us passes allowing us to move around the so-called dnr and russia.

After that, everyone who had passed the filtration was taken by bus to russia, and we were placed in a hotel. Our relatives had to pick us up from there. The hotel had no more rooms, so we slept in the lobby on sofas and armchairs.

After leaving Donetsk, my boyfriend and I made the decision to flee to Europe through russia. Our relatives in Donetsk, however, persuaded us to reconsider, insisting that there was no need for us in Europe. Despite their pleas, we were offered housing and job opportunities in Europe. Nevertheless, we maintained constant communication with our family, who eventually returned to Mariupol.

Unfortunately, the search for my father has proven to be an ongoing challenge. He resided in Strilka, and on March 13, he left home and never returned. His apartment was later occupied by members of the so-called dnr military forces. They forcefully entered the apartment, vandalizing it and stealing even the most insignificantly valuable possessions, including the icons.

In an attempt to find my missing father, my mother came to the Strilka district. Accompanied by my stepfather, they installed a new lock on the door. However, their hopes for protecting the property were quickly dampened when a neighbor warned them that their efforts would likely prove futile because the russians would likely disregard the lock and forcibly assign new occupants to the apartment.

Relatives say it’s hard in Mariupol now, there is not even enough food. The struggles are particularly challenging for my grandfather, who is a person with disabilities and a pensioner. Disturbingly, humanitarian aid has not been distributed to those in need. My grandmother was very supportive of russia, and now she cries all the time and says that the russians in Mariupol claim that we destroyed everything ourselves, so now we must rebuild it on our own.