Author: Natalia Kaplun, Yana Shynkarenko

Illustrator: Olha Panteleimonchuk

Snizhana Kovaliova (name changed for security reasons) was born in Transnistria. When she was 8 years old, her parents relocated to Mariupol, where she spent her school years. In 2014, Snizhana worked as a teacher in Donetsk, but had to return to Mariupol after the city was occupied. Unfortunately, on February 24, 2022, her life was once again shattered by russia.

Since 2014, the Vostok SOS Charitable Foundation has been diligently gathering information about war crimes, striving to ensure justice and uphold the right to truth.

The Foundation’s documentarian, Yana Shynkarenko, recorded Snizhana’s harrowing story, which was later penned by Nataliia Kaplun for the publication War. Stories from Ukraine.

In the spring of 2014, “little green men” arrived at the university where I was employed. They issued an order for us to vacate the premises, prompting us to relocate to the government-controlled territory. Subsequently, I made the difficult decision to resign from my position and return to Mariupol, where I embarked on a new path of social work. My focus was on providing assistance to women and children who had been affected by violence.

Before the tragic events of February 24, 2022, I resided on Azovstalska Street with my younger sister and beloved dog.

On February 24, the tranquility of our lives was abruptly shattered as planes began flying over our house, accompanied by a relentless symphony of explosions. My sister and I had undergone training on survival in the temporarily occupied territory, believing that we were prepared for any scenario that might unfold. We had packed our suitcases in advance and stocked up on essential supplies such as food and medicine. Despite the dire circumstances, we endeavored to maintain some semblance of normalcy, even continuing our daily routine of walking our dog.

As the conflict intensified and shops ceased their operations, we sought out local sellers who were kind enough to provide us with bread and water. Going to work became an impossibility. Subsequently, the basic necessities we often took for granted—heat, gas, and water—were stripped away, leaving us to contend with the harsh reality of survival. While the phone connection and electricity persisted for a while, even into early March, there were days when our only means of heating food was the microwave.

Regrettably, our house lacked a basement, further exacerbating our vulnerability. Moreover, a woman named Sonia who resided on the ground floor faced the same perilous circumstances.

On February 27, the first blow to our apartment came as a nearby airplane bomb shattered our windows. The inter-balcony frames were also destroyed, the air conditioner was dislodged, and our balcony was left punctured. In a desperate attempt to mitigate the cold and fear, we laid blankets and carpets in the corridor near the bathroom, where we slept on the hard floor.

The incessant presence of airplanes overhead instilled a constant sense of uncertainty. We were unsure of where we could seek refuge or find a safe haven. We briefly sought shelter at my mother’s house on Meotida Boulevard, but even there, we discovered no secure hideaway. In search of a reprieve, we spent three days in a bomb shelter on Pashkovskyi Street before mustering the courage to return home for the night, where danger continued to lurk ominously.

March 2 marked the beginning of a horrifying ordeal. The air was filled with intense shelling, and a neighbor from the second floor urgently approached us, informing us that we needed to seek refuge downstairs as Sonia had opened her room. Without hesitation, my sister and I decided to position ourselves near the bathroom, but the deafening sound of gunfire compelled us to grab a plastic chair and hastily flee downstairs.

Denys and Sasha, who resided on the first floor, joined us and offered to escort us to the entrance of Aunt Sonia’s house. It was during this harrowing journey that the full extent of the terror unfolded. Our house came under intense attack, and it felt as though each blow was directed at us directly. The very foundation shook, threatening to crumble beneath us. Denys bravely shielded us from harm as the shelling persisted for what felt like an eternity, approximately 20 agonizing minutes. Eventually, the intensity subsided, and Denys ventured out to plead for the door to be opened.

Inside the shelter on March 2, there were a total of 38 individuals, including 9 children, as well as 4 dogs, fish, hamsters, and a rabbit. The youngest child was a mere 2 years old, while the oldest was 17. Amongst the occupants were also frightened men, who rarely ventured outside, leaving me with the responsibility of managing and organizing the affairs within the shelter.

Denys and Sasha, who did not reside in the basement, ingeniously fashioned a makeshift brick grill at the entrance when the power and gas eventually ceased to function. It served as our means of cooking meals amidst the dire circumstances. From March 2 onward, the windows in the house were incessantly shattered, rendering any attempts at repair futile and impractical.

As the morning dawned around 7 AM, we confronted the grim reality of our circumstances. With no access to running water, we were unable to cleanse ourselves properly and resorted to using damp napkins for basic hygiene.

Our daily meals consisted of twice-cooked rations, but our supplies had dwindled to a critical level.

However, our dire situation took a turn for the better when a compassionate individual from the neighboring third block of flats brought us much-needed food, which sustained us until our departure.

Since the beginning of March, the scarcity of drinking water had plagued us. Yet, a glimmer of hope emerged in the form of a well located near Azovstal. Then we couldn’t leave the building, so we drained the water from the boilers and drank it. On March 8, when the snowfall arrived, we seized the opportunity to collect and melt snow.

We were given a large pot from a nearby kindergarten, which allowed me to prepare food for the residents of the basement. On the third day, I cooked a serving of buckwheat and appealed to the men present to deliver a bowl of food to a family with four children who had not sought refuge in the basement. Regrettably, their response was disheartening, as they expressed their fear, stating, “We won’t go – we’re afraid!”. I freaked out and called my sister. We looked and saw that the blast wave had deformed the door.

We knocked and shouted, Yulia was standing there, frightened, and the children ran out. She said: “Vova is wounded! I sent him to bring water and food, and he was shot in the leg near the store!”. Drawing upon our first aid training, my sister and I sprang into action. We swiftly returned home to gather crucial supplies, including medicine, gloves, and peroxide. Equipped with these essential items, we were prepared to administer immediate medical assistance to Vova.

On March 11, my aunt, her daughter, and grandmother sought refuge in the basement with us. Their own house had been tragically destroyed, adding to the devastation we faced. However, on that very same day, another profound loss struck our family as my grandmother succumbed to a heart attack. Filled with grief and the need for urgent assistance, we quickly arranged transportation and rushed to the hospital.

The scene that awaited us at the hospital was nothing short of harrowing. There were many wounded people there; everything was covered in blood. We found a worker and asked her to take the body. In response, she uttered words that left us stunned and disheartened, saying, “Are you kidding me? I haven’t slept for 15 days; no one is burying people now. Look!”. And I looked, and dead people were lying under the windows…

We made the difficult decision to wrap my grandmother’s body in plastic and leave her there. The uncertainty of her final resting place remains a burden we carry to this day. In an effort to ensure her identification, we meticulously noted down her information and our contact details, placing her pension card in her pocket.

The circumstances forced us to make unimaginable choices, overwhelmed by the sheer magnitude of the situation and the lack of available resources.

One day, Sasha, a worker at Azovstal, brought bread. Then there was a heavy air strike. He was killed. We could not bury Sasha.

The guys covered him with bricks so the wind wouldn’t blow away the blanket. He had two small children. He rented an apartment on the first floor. At night, he ran to his children on Kirov Street, carrying food and medicine.

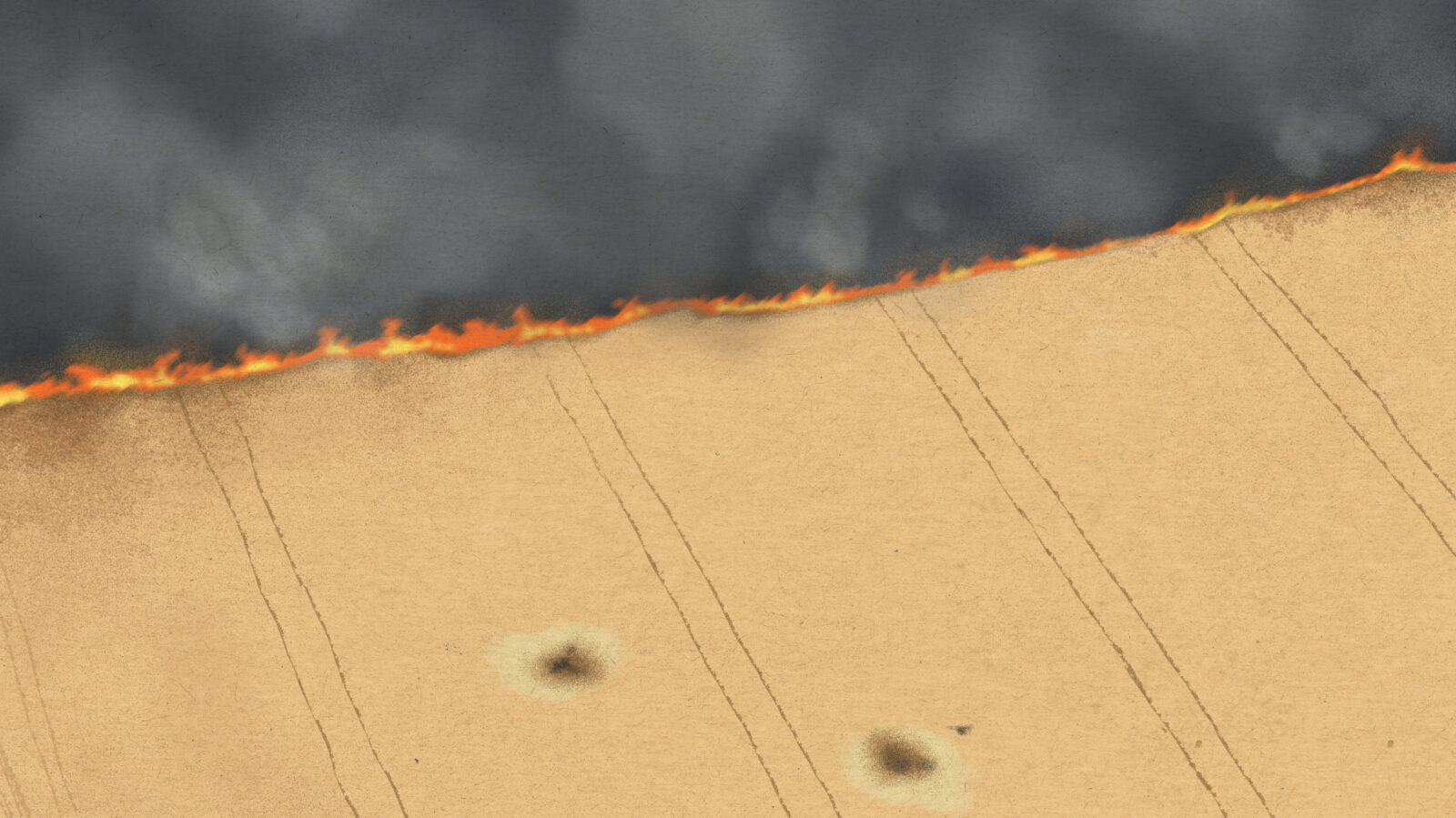

Towards the end of March, a dreadful incident occurred when the occupiers targeted a neighboring house, causing it to erupt in flames. In the midst of the chaos, a distraught woman and her son sought refuge in our basement. Tragically, their apartment was the first to succumb to the fire, and their beloved cat perished. It became clear that remaining in the basement was no longer a viable option.

We gathered all those sheltering with us and shared our decision to evacuate. Remarkably, almost everyone expressed their intention to join us. We collectively concluded that our best chance of escape lay in heading towards Vynohradne, an area already under occupation, as it was the only viable route available from the Left Bank.

After the shelling subsided, we made our way to Meotida Boulevard where my mother resided. However, as we stepped outside, we were confronted with the devastating sight of a tank striking her house. Despite the chaos, the basement of my mother’s house was already filled with people seeking refuge, but thankfully they allowed us to join them. Our original plan was to head toward Vynohradne on April 6, but circumstances delayed our departure, and we eventually left on April 7.

We reached the Pozhyvanivka church. A “dnr” checkpoint was nearby, and a volunteer was on duty there. He put older people in a minibus, took their bags, and drove them to the administration in Vynohradne. We got there at 11 o’clock; it was cold.

There we said goodbye to everyone, as we boarded different buses destined for either Bezymenne or Novoazovsk. We didn’t know where we were being taken, so we stayed together as a big family – my sister, mother, grandfather, aunt and daughter, and others.

Upon our arrival at Prymorske, located in the Novoazovsk district, we were escorted to a school facility. There, we underwent the registration process and received meager rations of food. The classroom assigned to us for the night offered no comfort, with only linoleum covering the floor and no beds or blankets provided.

The school premises were overflowing with approximately 600 people. Our sustenance consisted of a meager spoonful of buckwheat porridge. Although we had money, the villagers in Prymorske refused to accept hryvnias as payment for goods. Desperate for nourishment, we embarked on a village-wide search for food and a cooking vessel to use over a fire.

During our interactions with the locals, we encountered mixed reactions. In one house, we faced hostility and wishes for our demise solely because we hailed from Mariupol. However, in a neighboring house, the residents demonstrated remarkable kindness, offering us all they had—eggs, pickles, tomatoes, beets, and cabbage.

As we connected to a makeshift “Free Wi-Fi” nearby, we managed to communicate with our friends and acquaintances, who shared distressing accounts of the events unfolding in Bucha and Irpin.

Our departure from the school came about when we were rescued by our friends from Donetsk, who arrived in two cars. With the intention of reaching Georgia, we knew we would have to undergo a stringent filtering process. We spent 21 days in Donetsk, awaiting our turn. On the day assigned to us, we arrived at the filtration checkpoint at 8 AM, but it wasn’t until 4 PM that we finally reached the screening area. Our anxiety grew as we held tickets for Georgia, scheduled for the following day.

They treated us terribly… We were subjected to invasive questioning about the Azov regiment, and whether we had provided assistance to the military, and faced constant probing. I was nervous. When they took my fingerprints and ordered me to wipe my hands on the wall, I got scared and wiped them, but what could I say to people with machine guns?

To our dismay, they turned their attention to my youngest relative, who was 17 years old at the time. They shouted at her to recite the poem Borodino. She replied: “I didn’t learn it at school, but I can recite Shevchenko’s poem”. They forced her to write, and the child wrote in Ukrainian, including the letter “i”. They yelled at her: “Correct it. I don’t know these letters!”. Refusing to yield, she stood her ground, sparking a heated argument. Eventually, the occupiers relented and allowed us to proceed.

The following day, we embarked on our journey to Georgia. As we approached the customs checkpoint, most individuals were allowed to pass through without any issues. However, my sister and I faced a different fate. Our passports were confiscated, and we were led to individual booths for further inspection. They checked our phones and everyone’s names on the list. Then they asked, “Why are you single? Where do you work? Have you fed the military? Who is standing on the street?”. The conversation lasted about 40 minutes. Thankfully, in the end, they returned our passports, allowing us to continue our way.

Upon reaching Germany, we were confronted with the harsh reality faced by those who remained in Mariupol. Heart-wrenchingly, we received the devastating news of our close friend’s passing on her own birthday. The photos we saw portrayed the utter destruction that befell our once-beloved home. While my mother’s house also suffered damage, there are plans underway to restore it.

However, in light of russia’s continued presence, we have firmly resolved not to return. This stance represents our unwavering moral position.