Photos by Katya Moskalyuk

Alina and her six-year-old daughter Kamila are from Kharkiv. Their house is on the outskirts of the historic neighborhood of Kholodna Hora. There’s a tank factory nearby, a potential target for enemy shelling. When the war started, Alina picked up a bag with basic necessities and took her daughter to live with her mother in the center of Kholodna Hora. They lived there for three days and went down to the basement every night.

When the full-scale war started, Alina tried to hide it from her daughter. When they were going down to the subway station for shelter, Alina told her daughter that it was a rehearsal before a camping trip or a jacket party.

“There were explosions all the time,” recalls Alina. “On the last day in Kharkiv, at 4 a.m., a missile flew over our building. Everything was buzzing from the sound wave. The missile fell about 500 meters away from us. Next to the school where we had intended to go.” The woman was ready to leave the city right away with her child, but her mother couldn’t dare to do it for a while. But after the missile exploded, she had no doubts anymore.

Alina moved her things to an even smaller bag to make it easier to carry, and she, her mother and daughter ran to the train station. Her niece and her aunt joined them there. The evacuation train arrived in 15 minutes. “We were traveling in a compartment with about 20 people in it. My kid couldn’t even get up once in those 24 hours, she only ate a yogurt. We couldn’t reach the sandwich which was in the bag,” says Alina. Her brother stayed to defend Kharkiv.

“We were traveling in a compartment with about 20 people in it. My kid couldn’t even get up once in those 24 hours, she only ate a yogurt. We couldn’t reach the sandwich which was in the bag.”

Now Alina and her family live in a photo studio which was turned into a shelter for mothers with small children. Alina has no plans for the future yet. Maybe they’ll go to Poland, she says. But for now, going to the train station is scary: she’s afraid her daughter will be killed in the stampede.

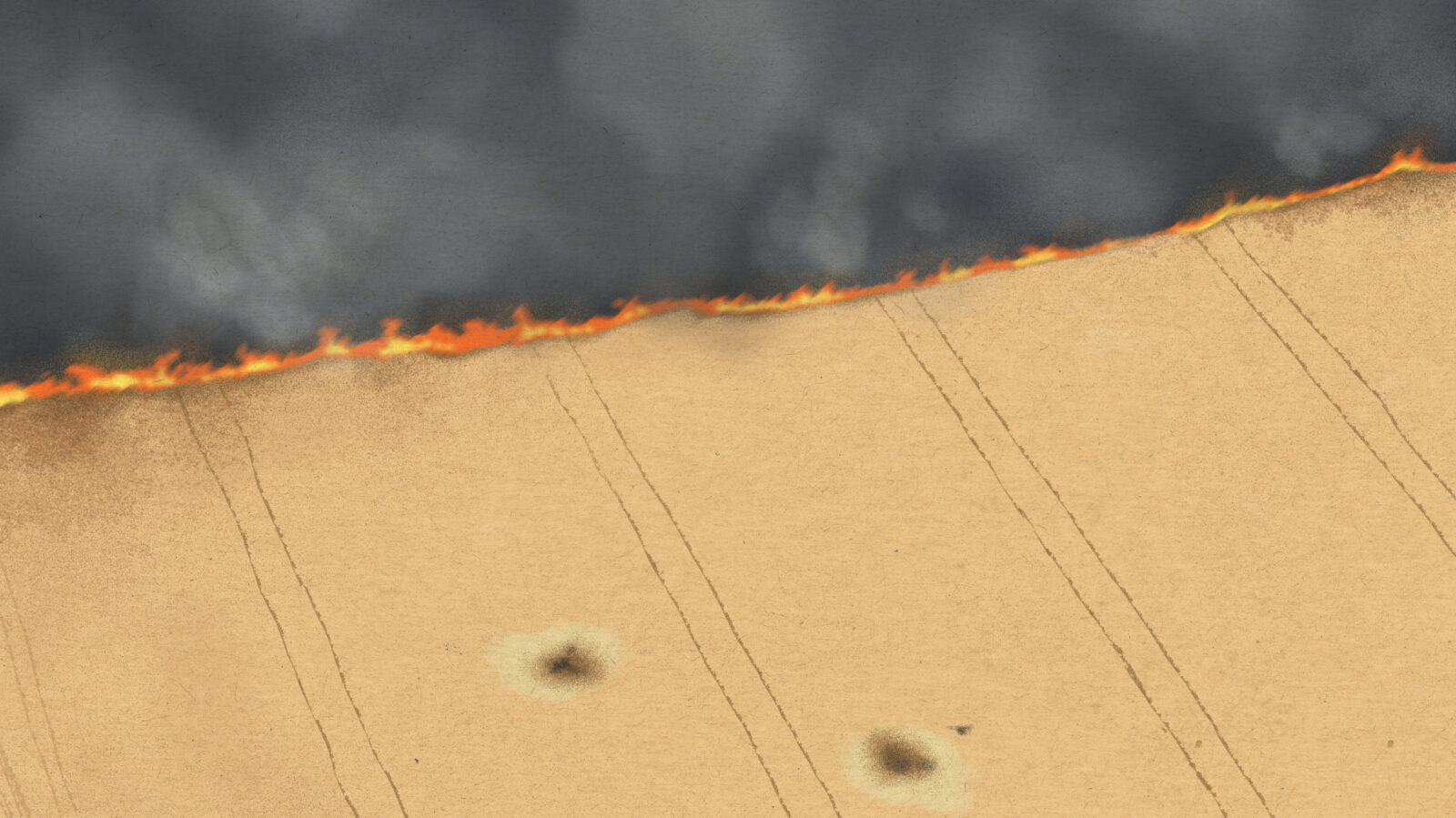

In peacetime, Alina worked at the market, selling molds for cake making, spoons, forks, home decorations. Both her job and her apartment are still in Kharkiv. There’s no power or water in the city, the stores are empty, people are running out of food and staying in basements. The market where the family used to buy bread before they left has already been destroyed. As well as the neighboring building where Kamila used to play in the sandpit.

Alina occasionally calls her friends in Kharkiv. Many of them have left for Poltava, some have moved to the outskirts of the city, some have stayed. Her friend’s six-year-old kids can already tell the difference between the sounds of the different multiple rocket launchers: Grad and Smerch.

Alina can hold on thanks to the support of her family with whom she left the city. But she is worried about her brother. She also recalls how before the war, she wanted to take her daughter to the circus and the theater, but they could not. In Lviv, she was struck by the number of cars. Because in Kharkiv, a hot spot, the locals always peeked out the window to check who’s coming whenever a car was passing.

Kamila’s birthday is coming soon. Her present is still at home, in Kharkiv.