“I learned by chance from social media that a shell hit our apartment in Mariupol and it burned down. My grandmother could have been in the apartment. We asked her to go down to the shelter, but whether she was there at the time of the attack is unknown. I haven’t been in touch with my family for two weeks now,” said Kateryna Radyk, 21.

In the besieged and bombed-out Mariupol, she has two grandmothers, a grandfather, an uncle with a young family, many friends and a best friend, who was preparing for her wedding in February.

“Just before the war, she and I were looking for tickets to Italy to organize a wedding there in March. I don’t know if my friend is alive now. She lived next door, checking on my grandma under the shelling until recently. I learned from photos online that there is a huge funnel from the explosion in her yard, and the connection with my friend has been cut off.”

Kateryna herself has lived in Kyiv for several years, studied culturology and worked in the field of culture. In the first days of the war, she even planned to go to Mariupol, believing that it would be safe there, because in the past 8 years the city has learned to live under a possible threat of shelling. But then the electricity went out in the city, and Kateryna lost touch with her entire family. Only her friend called sometimes.

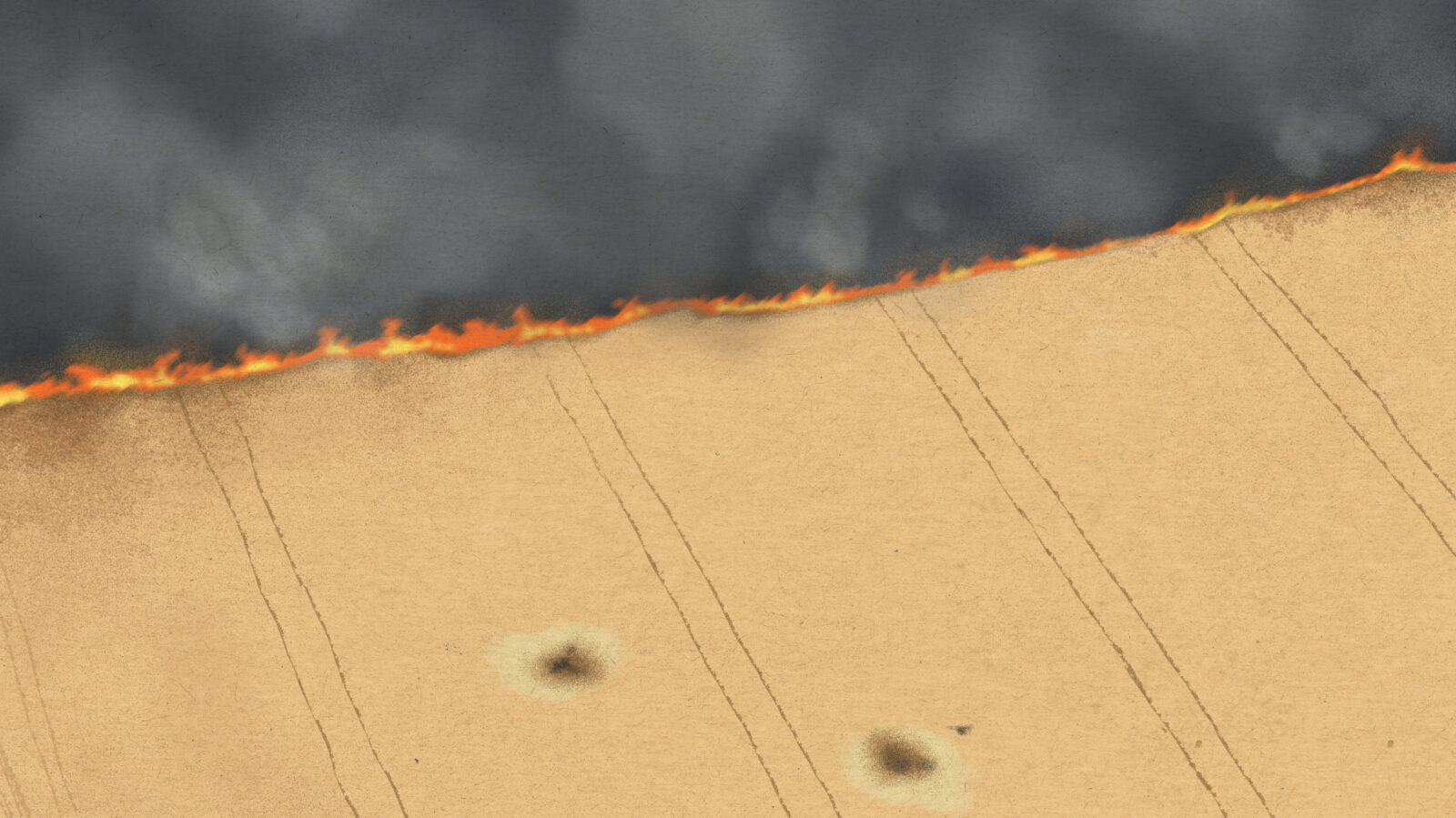

“She went to see my grandparents, despite the fact that the house opposite theirs was already on fire. She saw a projectile hit it with her own eyes. People in Mariupol got used to the war and were not as afraid of shelling as in most of Ukraine. That is why many Mariupol residents did not go down to shelters until the last minute and did not want to leave. Perhaps this is a form of post-traumatic stress disorder—a muffled sense of self-preservation. That’s why my relatives didn’t leave when it was still possible,” Kateryna says.

For some time, there was a weak cell phone reception in Mariupol near the former office of the mobile service provider. People from all over the city used to come there just to send a short text message to their relatives: “I’m alive” or “Our house is still standing.” However, it was risky to go there: the city was shelled every 30-40 minutes, so you could die on the way. Then even this possibility disappeared.

“As far as I know, people in Mariupol are now drinking water from heating mains and melting snow. The big question is what they eat, because the stocks have run out a long time ago, no stores are open.”

Together with her parents and her younger brother, she lived in Kyiv for about a week in a shelter at a nearby school. The last straw was when looters tried to break into her rented Kyiv apartment.

“I went up to the apartment to take a shower and change my clothes after a week in the shelter. I was alone in the apartment when some people started breaking the door. I was very scared. Fortunately, they did not manage to break into the apartment and fled. My neighbors later said that they were looters posing as utility workers or territorial defense to get into buildings.”

After this story, Kateryna’s family decided to move to a safer place. They managed to find a carrier, but the bus was not allowed to go through at the checkpoint. They had to spend the night at the Teremky subway station.

“We simply didn’t have anything for that. We stayed all night in the subway without heating. It was hard, but it was only one night. I can’t imagine how hard it is for people in Mariupol who have been living like this for two weeks now,” says Kateryna.

Now she is in Germany, staying with friends. Together they’ve created a charity project—the sale of NFT drawings, all funds raised are directed to support the Armed Forces of Ukraine. She also contacts foreign journalists and tells them about the situation in Ukraine, because she is convinced that only public pressure can force European leaders to help Ukraine even more actively in various ways. Katya is constantly looking at photos and videos from the besieged Mariupol, hoping to see her relatives there—alive and unharmed.

“I do not plan to stay in the EU. I hope that very soon I will be able to return to Kyiv and rebuild Ukraine,” she says.