Illustrated by Liubov Miau

The morning of February 24, my wife took our son to school while I was still asleep. My wife came back at around 8 a.m., and immediately after that our son’s teacher called and said, “The war has begun.” And we just… Explosions, oh, explosions. We’ve always heard them from the left bank, although the past few years it’s been quieter. My wife immediately called Senya [son, 14 years old], told him to wait at the bus stop and ran to get him.

I worked at an aquarium shop where I sold fish, plants and feed. That morning I wrote to my boss and asked if I should come to work. He replied, “What do you mean, work? There’s a war!” I mean, I didn’t really understand what was going on. But the same day, even stronger explosions began. The war came to the entire Ukraine. I hadn’t smoked for 10 years, but on that day I started again.

On March 2, our electricity, heating and cell connection were gone. On March 6, an old friend of mine, with whom we had not spoken for 5 years, came to see me. The three of us were sitting in the kitchen, drinking, and my wife was heating water. We still had some tap water stored. Gradually the gas went out.

We slept on the floor in the apartment, under 3-4 blankets. We went to get water from the well and cooked on an open fire.

We bought some potatoes, onions and carrots when we still could. My friend brought some lard and sausages. I’ll be honest, our neighbors looted the store and gave us some food. The Orthodox Church gave us two cans of peas and two cans of corn. They also cooked some soup—a small serving, but at least you could eat something. We didn’t take food, we only signed up for humanitarian aid. But the Russian bastards did not let it come through. We made some rusks while we still had bread. We would cook some soup on the fire, throw some rusks in it, and that was our lunch. We had some flour, so my wife would make simple pancakes: flour, salt and water.

I hadn’t talked much with my neighbors before, a lot of them were pro-Russian. But when the war began, it turned out that they were more or less normal people. War, you know, makes people more humane, they start helping each other, they get closer. Although people are different, some people make money off the war.

Most of the time we stayed at home because our bomb shelter was very damp. We went down there only when they fired directly from Grads (multiple rocket launchers). I felt the first serious bombing when we went to see my friend’s mother. A plane dropped a bomb near the pier, near a viewing platform, it was 300 meters away from us. It was the first time when we got very scared. Later we also went to the city center to see my wife’s mother. There were very serious battles in all the yards, I called it ‘the little Grozny.’ Cars and houses were on fire. We made our way out running in-between shellings, through the yards. We’ve seen people cooking meals right next to graves—one for an adult and one for a child.

Another time, when we went to check on my wife’s parents, we saw a huge puddle of blood, and in it a brain, you know… yes… just floating. There were a lot of corpses in the city: at bus stops, on benches. They would be wrapped in blankets and taken out. Next to my house, there was a woman’s corpse wrapped in a blanket. It stayed there for 5 days. Next to her, someone made a cross from two twigs. Then, I guess, her relatives decided to bury her. They dug a burial pit in a chestnut alley and buried her among the trees.

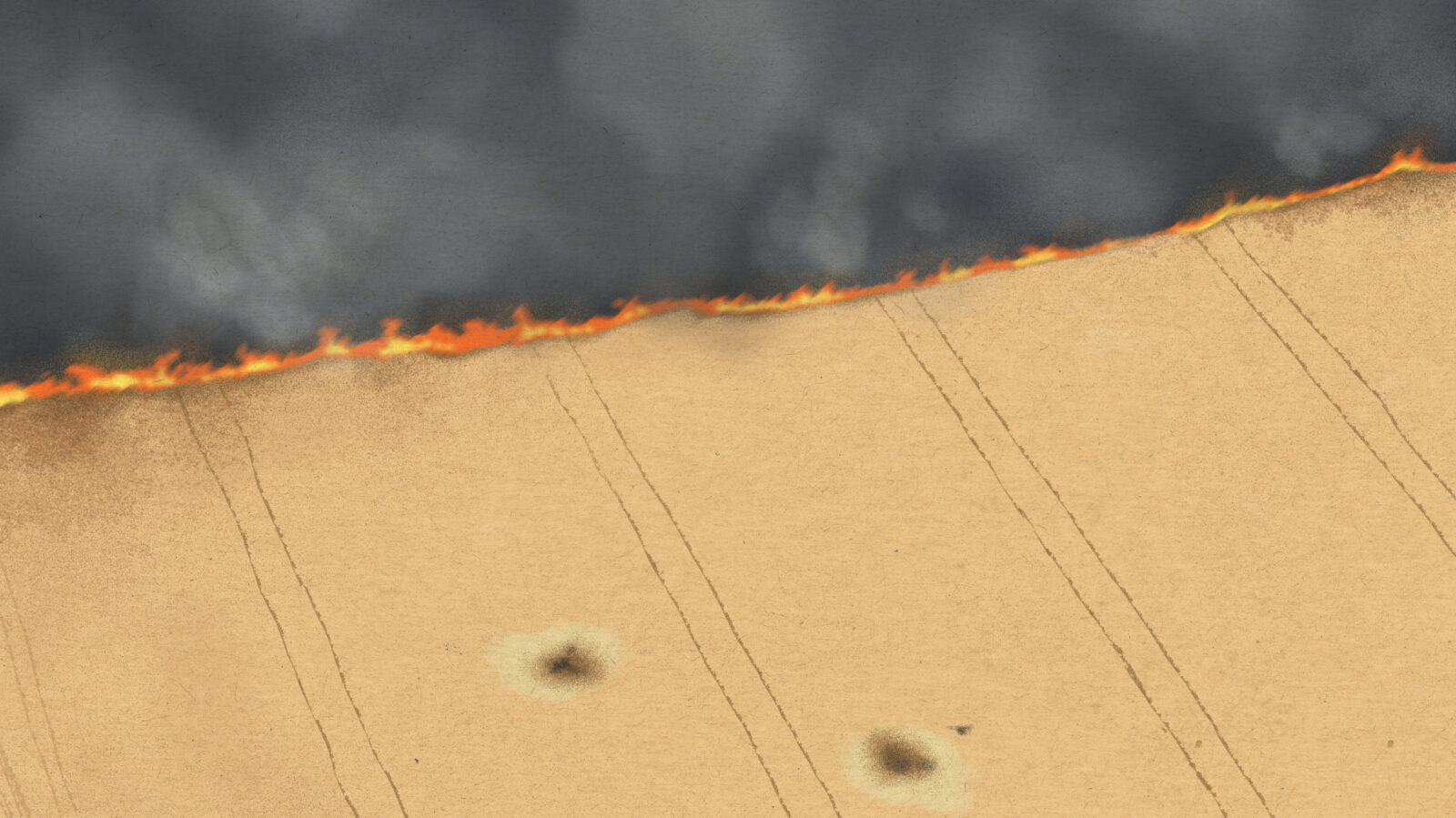

One day we were cooking a meal in the yard. We lived opposite from the shipyard. A shell flew into the shipyard, there was a strong explosion wave, and we ran to the porch. We were a little scared, but we thought, “Okay, it hit the building, but it’s more or less okay.” We went out and continued cooking. After that, we went home and heard such a loud bang. The missile hit the 9-storey building behind our house, it burned down completely, and the roof of the house next to it was demolished. After that, we decided that we had to leave.

I didn’t have a car, so I talked to our neighbors, but some of them took their papers, mattresses or other junk with them, and there was no room for us in the car. Their belongings were more important to them than human lives. A neighbor with a child was also looking for a place in a car for them and could not find it.

Finally I managed to find a man who agreed to drive us out. We drove from Mariupol through Milekino. There was a Russian checkpoint on the side of Zaporizhia. In Mangush, there was a “DNR” checkpoint with a Russian flag on it. In Ostapenko, there was a Russian checkpoint. But the checkpoint in Berdyansk was the scariest. It was manned mostly by Buryats. They asked me to show my tattoos, they were checking if I was from the Azov regiment. I showed them my tattoo, then they sent me to register. It was like in Schindler’s List: three plastic tables, three Russian soldiers sitting, a notebook and a pen. They asked for a phone number, name, year of birth and city of residence. They checked whether you had been in the military in the past 8 years, well, you get it—all this is shitty propaganda. I filled everything out and went to Berdyansk. We lived there in the local house of culture.

We stayed there for 4 days. For a long time we were looking for an opportunity to go to Zaporizhia. And it happened. Then there were checkpoints again. Some soldiers were looking through our messengers, photos, others checked our tattoos again. In Zaporizhia, we got some water, food. They took us to a kindergarten where we could sleep. There we took a shower for the first time since February 24.

My son is taking everything that has happened easier than the rest of us. My wife is suffering the most because her parents are still there. They did not want to leave. They said, “Our belongings are here, we don’t want to give anything away, everything will be back to normal.” My parents have also stayed there. Mother called today and said that it was still quiet near them.

I miss the city, even though it’s been killed, even though there was nowhere to shower.

Translated by Tetiana Sanina