Illustrated by Liubov Miau

“Grandma, do you mind if I write a short text about you?” I asked my old grandmother during our first conversation after a long four-day break. In the Kharkiv area, where they live, there was no power, so charging the phone was impossible. We didn’t know where they were and whether they were okay.

“Well, write it. But don’t write that it’s fine here. Say it this way: my old grandpa and grandma have been living for four days with no light, no information. The TV and radio don’t work. They live by candlelight.”

I write it this way: it’s not fine there.

My grandma Alla, who comes from Lugansk Region, is 84, and my grandpa Tolya, who was born in Sumy region, is 89. Both spent their childhood listening to the sounds of World War II shelling. And now the missiles of the Russian occupiers accompany their retirement. Grandma says that she has seen many faces of Kharkiv since she moved here in 1959. But now, looking at the photos of the ruined city, she sheds tears.

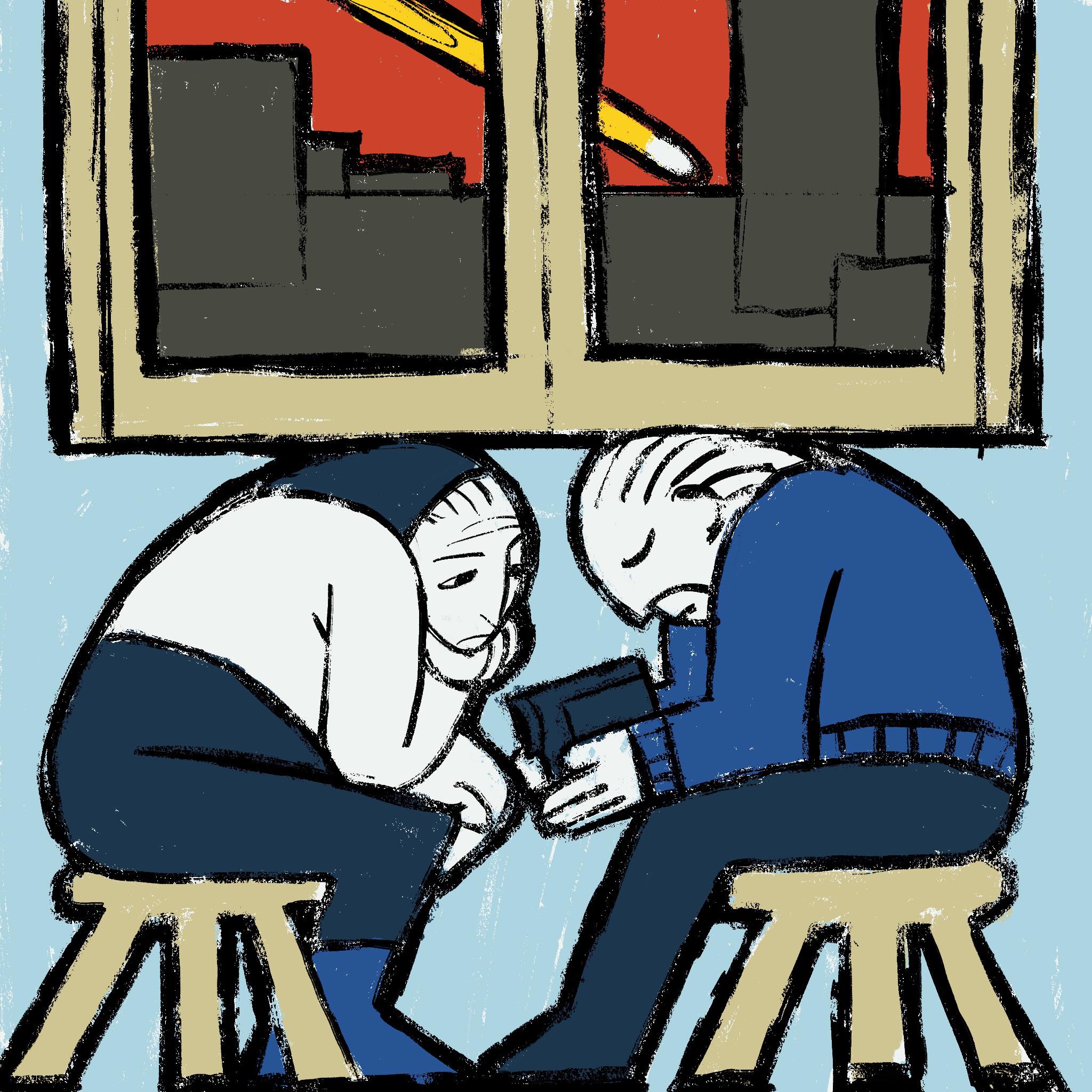

They don’t go to a shelter, afraid that they won’t have enough time to reach it, so they move to the hallway during shelling. It is hard to sit there for a long time: there isn’t a lot of room, the stools are uncomfortable — their legs swell and their backs hurt. The windows of their apartment, facing three sides at once, are still unsealed — grandma thinks that sealed windows will help the enemy to determine where to shoot, so she refuses to seal the glass. They try not to go out in the street, although they decided to take the risk on the last winter day.

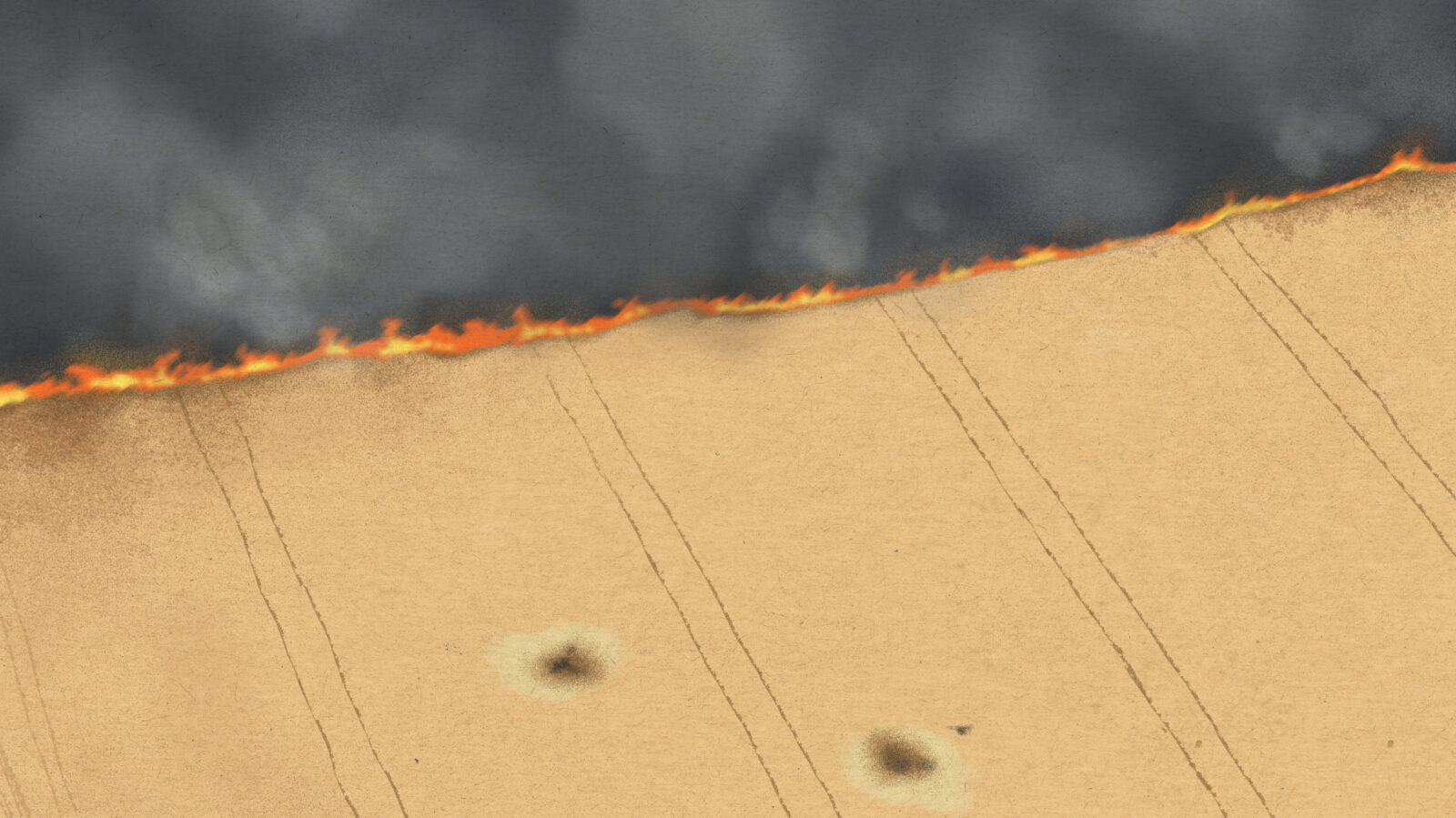

“We didn’t go out for a long time, because there were explosions all the time. But then I thought: alright, let’s do it. First, we had to walk at least a bit, and second, maybe we’d buy something green. We came out, and the neighbor downstairs said: ‘Where are you going? You shouldn’t.’ I told him: ‘Don’t worry, Zhora. We’ll take the garbage out and have a look.” The garbage was taken out, everything was quiet. We reached the supermarket, it was closed but there was a line in front of it. The street market was also empty. So we went home. And there, we found out that two missiles were stuck in the ground just next to the market where we’d just been—they didn’t explode, but another one did, a bit further.”

They will have enough cereal and frozen meat for a month. Meanwhile, their neighbors bring them food whenever possible: sometimes eggs, sometimes fresh bread. The refrigerator, bought a couple of months before the war, kept the temperature in the freezer for four days without power, and now my grandmother talks to it, passing by: “What a miracle you are, thank you so much.”

Our grandparents have serious plans for “after the war”. Grandma dreams of going to Russia and to defile Putin’s grave in some creative way, and grandpa wants to give me his biggest treasure for my birthday: a video camera which I left in Kharkiv as a guarantee that I would return to my city, to my people. While there are kilometers of sky, cut by sounds of sirens, between us, I think about the unsealed windows and that video camera, which I will definitely use one day to record my grandma and grandpa and the rebuilt Ukrainian Kharkiv.